Oscar Watch: How BlacKkKlansman‘s Composer Channeled Jimi Hendrix’s Iconic Riffs

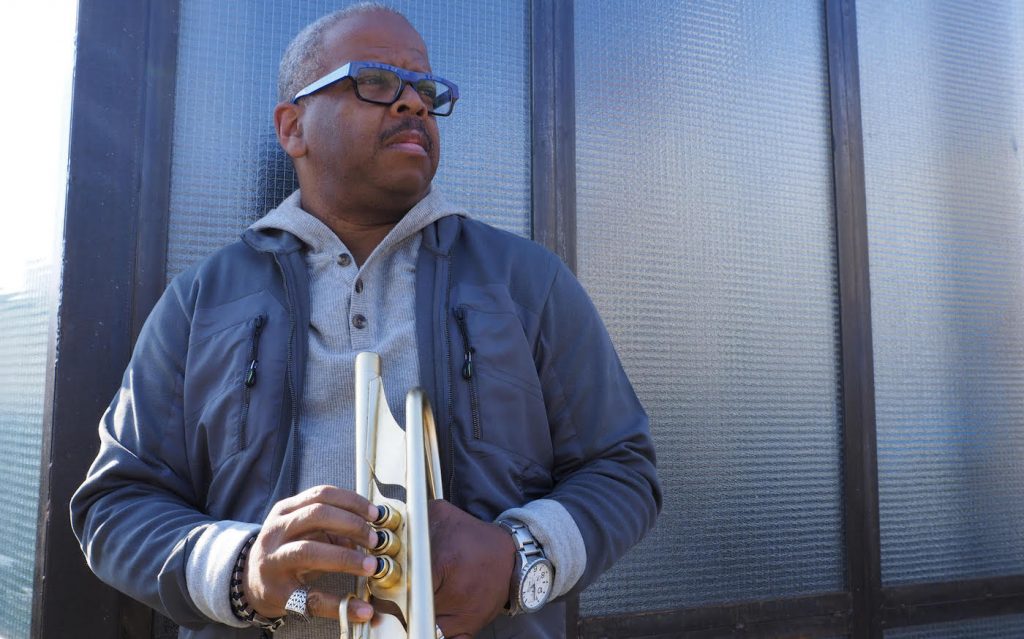

Terence Blanchard landed on this year’s Best Original Score Oscar shortlist by crafting the stirring score for Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman. Based on a true story and set in 1971, the movie casts John David Washington as Ron Stallworth, a black cop who infiltrates the Ku Klux Klan with his Jewish colleague (Adam Driver) by impersonating a white supremacist over the phone. Blanchard, a jazz trumpeter who grew up in New Orleans alongside Wynton Marsalis, has served as Lee’s musical alter ego for nearly three decades, scoring 18 of the director’s previous projects dating back to 1991’s Jungle Fever.

Speaking from Washington D.C., where he’s playing gigs with his E Collective quintet, Blanchard discussed Jimi Hendrix’s influence on the killer guitar riff that drives the BlacKkKlansman score and drills into the emotionally-charged finale featuring news footage of the 2017 Neo-Nazi Charlottesville riots.

You get a lot of mileage out of “Ron’s Theme,” the guitar riff that recurs throughout BlacKkKlansman. What were you aiming for when you came up with that motif?

I was trying to create something, I don’t want to say mournful – – melancholic I guess in a way. At the same time, I wanted Ron Stallworth’s character to have some strength about him. When Spike first told me about Ron I thought he was pulling my leg. This black rookie cop going undercover with the Ku Klux Klan—that takes a set of balls I can’t even imagine.

So you’re sitting there at the piano and . . .

I wanted the theme to be bluesy and it just fell into place. I knew the motion of going from C major to Ab major would have a certain kind of line to it.

You wrote it on the piano but heard that theme being played on electric guitar?

Yeah. Part of the inspiration came from me thinking about Jimi Hendrix playing the national anthem at Woodstock. Growing up in the south, that was one of the most patriotic things I’d ever heard. “Look, dude, we’re all Americans, we’re all in the same boat.” That’s what I took from it. So when Spike came to me with BlacKkKlansman, I said, “Well we haven’t done electric guitar yet” and he said, “Alright let’s go for it.” I knew Charles Altura would take it to another place on guitar because he’s a great musician. He makes it his own. The whole band does that. We were in Europe for three weeks before Christmas and whenever we did an encore, the guys in the band—not me—wanted to play Black Klansman as their encore. They’ve really taken ownership of it.

How did you integrate the sound of your E Collective bandmates — guitarist Charles Altura, drummer Oscar Seaton, and bassist David Ginyard — with this full-blown 65-piece orchestra?

Like I always tell my students, musical ideas are malleable. I did not try to get the orchestra to do what the rhythm section does and I’m not trying to get the band to do what the orchestra does. I used each group for their strengths, not their weaknesses. So maybe one time I’d have the guitarist playing the melody just with the orchestra because we needed that color in the scene. Or else the band starts out and then the orchestra comes in and takes over. You take all these elements and intertwine them in such a way that the music becomes something unique.

At one point, for example, it sounds like you’re backing up the guitar riff with powerful, low-pitched horns.

What you’re hearing there are tubas mixed with two trombones and French horns. Working with Spike on his films, he’s always wanted to show the majestic nature of these human stories. Early on, I learned how to use [orchestral] colors and move harmonies in a certain way so they create emotional reactions in the audience.

BlacKkKlansman opens with the famous battlefield sequence from Gone With the Wind, accompanied by your orchestration of “Swanee River.” A lot of people associate that song with the Old South. Was it weird for you as a black man to orchestrate and conduct this particular piece of music?

I’ve been waiting for somebody to pick up on the irony of that, which I find fucking hilarious. Dude, I grew up in the south in the seventies. I remember a gig where one of the musicians played [Blanchard hums “Dixie” melody “I wish I were in the land of cotton”] and people in the audience cheered. So I’ve been around that all my life. When it came time to score that scene, I didn’t necessarily want to do the orchestration but if I wanted the rest of the movie to make sense, I had to make the song be the best it could be. It was a matter of taking my history and my emotions out of it and saying, “Okay I know the sound from what I heard it as a kid, so I’m just going to go ahead and create this piece of music so it can lead into the rest of the film.”

You did the job without embracing the sentiment.

Yeah. The other thing too is that I looked at the actors who played the Klansmen. They’re very convincing, but I met those dudes and they’re very nice, man [laughing]. So I took my cue from them.

Where did you record the music for BlacKkKlansman?

The band was recorded in New Orleans and we recorded the orchestra in L.A. at the Sony soundstage.

Was it important for you to work with live players rather than programming music samples with a synthesizer as a lot of composers do these days?

I’ve always loved the process of working with live musicians because when I compose music, I know what its supposed to do. But when you put the music in front of great professionals, the pianissimos become more subtle, the swells become real emotional movements and the whole experience becomes bigger than what you imagined. You’ve got to remember, I’m a jazz musician, so part of that experience is that we allow people to bring to the music what they want to bring to it.

BlacKkKlansman ends with a wallop when Spike Lee cuts from Klansmen chanting “Blood and Soil!” around a burning cross in 1971 to Neo-Nazis chanting the exact same slogan in 2017 at the Charlottesville riots. What was it like scoring that sequence?

It was hard to watch over and over again because you’re looking at actual footage of people fighting and being hit by a car in the United States of America, in 2017! I’ve discussed this with my friends, how they’d be watching the movie and enjoying the Afros, the bell bottoms, reminiscing, and then all of a sudden it cuts to the present day and you go “Wow, this is still happening 40 years later.” When that montage comes on, it makes you realize that as a society, we haven’t grown as much as we thought.

In Black KkKlansman, characters constantly throw around the N-word. How did you respond to that language?

I grew up in Louisiana hearing that shit all the time. For me, the N word just put me more in the mindset that people who see this film need to feel the sting of it. I remember playing trumpet with Lionel Hampton’s big band in 1980 at the Roosevelt Hotel. My dad walked up the hotel stairs with me and started to cry. I was like, ‘Man you got to chill out.’ Then he told me he used to work at this hotel but could never walk through the front. He had to walk through the back service entrance, only come out to the ballroom to bus the tables and then go back into the kitchen. And now he’s going through the front door to see his son play in that same room. Those are the stories that resonate when I hear the N word in this film. We have tons of those stories like that throughout my family. It’s the emotional engine that drives all of our efforts in this movie.

So you were able to use these personal histories as inspiration for your music?

Not just inspiration but a kind of redemption for all the people who have had to go through experiences where others try to make them feel less than. And now, we’re trying to turn the tide on all of that stuff.

Featured image: Director Spike Lee and actor John David Washington on the set of BlacKkKlansman, a Focus Features release. Credit: David Lee / Focus Features