Documentarian Morgan Neville on Revealing Mr. Rogers in Won’t You Be My Neighbor?

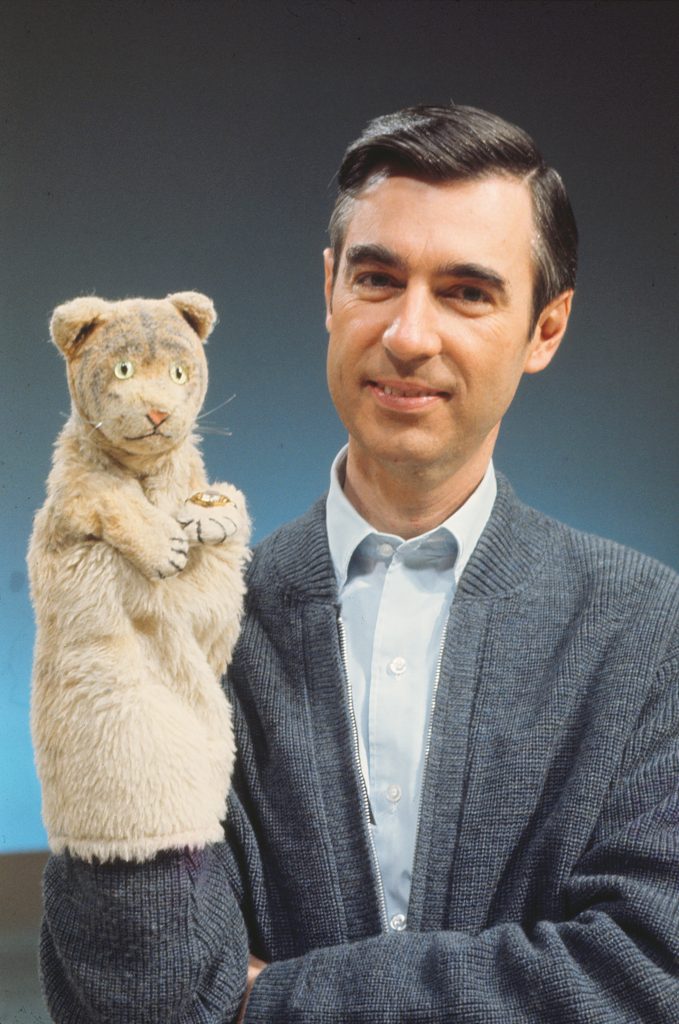

Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, which premiered 50 years ago on PBS, is undergoing a bit of a renaissance of late. Although host Fred Rogers died at age 74 in 2003, his effect on the lives of adoring preschoolers and beyond is still being felt. Earlier this year, PBS aired It’s You I Like, a tribute show named after one of Rogers’ many self-penned songs that he performed on the series. The U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp in his honor. Most PBS stations carry the popular animated spinoff, Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood, that debuted in 2012. Mr. Rogers is even available in Funko Pop doll form these days, complete with his trolley. And Tom Hanks will play the man himself in the upcoming feature film You Are My Friend.

But there is no better way to experience the real deal within the context of learning how Mr. Rogers the TV star came to be and why he had such a profound influence on his audience than Won’t You Be My Neighbor? The documentary is directed by Morgan Neville, the man behind the 2013 Oscar-winning doc about back-up singers, 20 Feet from Stardom. After a glowing and tear-filled reception at this year’s Sundance film festival, Won’t You Be My Neighbor opens on June 8. Neville speaks about why he thought his topic would be timely, how he earned the trust of Rogers’ widow, Joanne, and how the show affected him as a kid.

A lot of us are trying to make sense of the world right now and I feel gaining new perspectives drawn from reality-based entertainment helps somewhat. Your film definitely lifted my spirits while reminding me there was a time when we weren’t so divided about what matters.

That’s part of why I made the film. That reaction. I can’t believe how contemporary this story is even though it features a character from 50 years ago. A big part of my motivation to make it was that, a couple years ago, I had a feeling we needed a discussion about stability, something important that Fred Rogers talked about. What kind of neighborhood are we going to have? We seem to have so little common ground with each other now. I didn’t know that the show’s 50th anniversary was near when I thought about doing it. But when I realized it was, I knew it would be silly to put it out the year after. I thought, “Just let me get it done.” It came together pretty quickly and I was glad we made it to Sundance.

In 1991, I got to interview Mr. Rogers for USA TODAY at Pittsburgh’s WQED and watched a taping. I played with the trolley, checked out his sweater closet and hung out with David Newell (Mr. McFeely, the delivery man) and Johnny Costa, the piano player and musical director. But Fred was under the weather and the taping didn’t go very smoothly. When we did finally talked, he ended up asking me more questions about myself than I asked him. It was frustrating as a reporter but that is who he was.

That is very typical of him to not want it to be about him. He would rather hold up a mirror. He often carried a camera out in world and would tell fans, “Let me take your picture.” It was a defense mechanism. He didn’t want it to be about him. He so wanted to shine a light elsewhere. When I first talked to Joanne, I told her I want to make a film about his ideas, not a biography. He always said his story was the most boring ever. There was a consistency to him. But it didn’t take me long to find a few clues that suggested there was a lot more going on with Fred Rogers than he would let on.

You were born in 1967, the year before the show premiered. Did you watch it as a kid? You have said that classical cellist Yo-Yo Ma inspired you to consider Fred Rogers as a subject. You asked him how he dealt with fame as a young prodigy and he said Mr. Rogers was his mentor after he was on his show several times.

I was really into him – I was a big fan at ages 2, 3 and 4. I really loved the show. I got to thinking about him and having a serious filmmaker making a serious film about Mr. Rogers. My wife was the first person I mentioned it to and she loved that idea. It gave me confidence that others perceived him the same way. I knew from my research that what was most important about him were the things he talked about. He had a steel backbone and was really motivated.

I think using Daniel Tiger, one of the puppets that Mr. Rogers voiced on his show, as a cartoon avatar in animated segments that reveal his own insecurities and fears as a kid was a very helpful tool to better understand him.

I had an idea early on when I knew his own childhood had shaped him and his work for the rest of his life. What qualifies you to be Mr. Rogers? I was a child once in touch with that. You can see it all through a prism and Daniel is a perfect stand-in for that.

How did you win the trust of Joanne and others who were close to him?

The most important part of what I said before I made my pitch was that this would be about his ideas. That they responded to. For an estate that is very protective, they had to give up all control to me. That was my condition and they did it. It also helped that Yo-Yo Ma’s son, Nicholas (who, as a kid, was on the show with his dad), was my producer and acted like an emissary. Also, they watched a number of my films before agreeing. They got it. Once they decided to work with me, the floodgates opened and my access to everyone couldn’t get any better.

You probably viewed hours upon hours of old clips and episodes. What happened when someone is so exposed to Mr. Rogers and what you have called his radical kindness? Did his attitudes rub off?

There was a team of us going through the footage The producers and me went through everything, all 900 episodes. So many things were gleaned from that. We also dug deep into other odds and ends – speeches, home movies and outtakes. All that stuff that archive documentaries live and die by. If you actually look on the surface, the show never changed and he never changed. But you also realize that it absolutely changed in subtle ways. He became much more strident in what he was doing. The other effect was that we felt like we got to live in his neighborhood for a year. His influence trickled down. I never had such a warm group and such a huggy production. It was the perfect bubble for 2017.

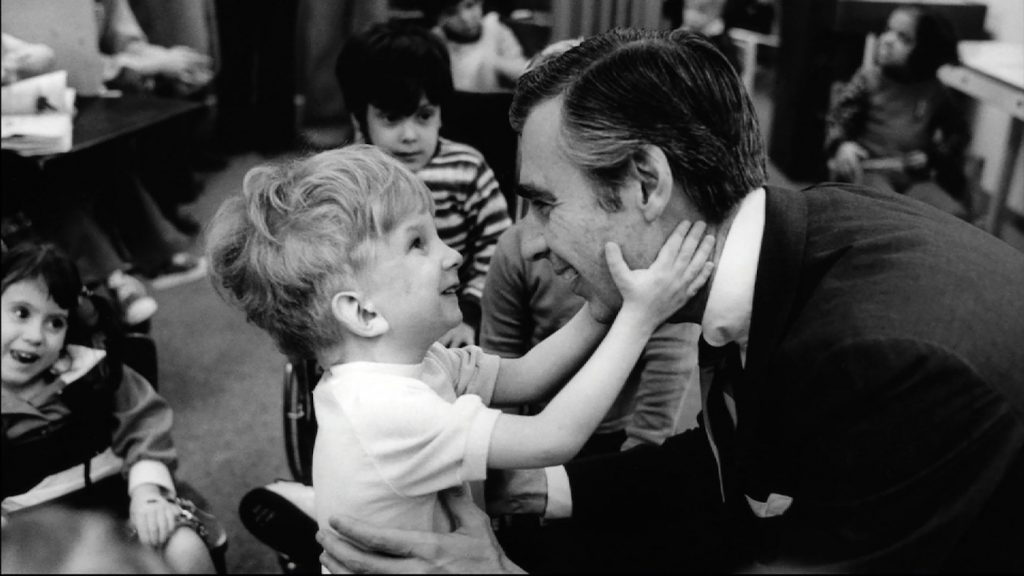

You did reveal a few of Mr. Rogers’ warts. Such as how he told Francois Clemmons, who played a black police officer on the show, to hide his gay lifestyle outside of work in order to not upset sponsors like Sears — even to the point that he was married to a woman for a while. But, as Clemmons said, Mr. Rogers later accepted him and told him he loved him just the way he was.

The thing that Joanne said to me when she decided to make film was, “Don’t make him into a saint.” Fred the human did not exist on a different plane. He struggled with insecurity from his earliest days to his death bed.

I appreciated that you included how people questioned whether Fred was too good to be true. Or as late-night host Tom Snyder put it, “Are you square?” Some even thought he was gay. When I asked Joanne about what he actually changes into when he gets home from work, she said instead of a sweater and sneakers, he put on a “casual jumpsuit.” I can’t tell you how many of my co-workers took that as a sign he was gay. Just because he was soft spoken, open-hearted and cared about feelings and lacked the usual aggressive macho instincts of many men, he was suspect somehow.

We had to include that. The real question everybody had was, “Is this guy for real?”

For your next project, you are doing a documentary about Orson Welles, They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead. What direction will that take?

It will be out before the end of this year. It is a film within a film within a film. It’s about the last movie Welles tried to make and never finished, The Other Side of the Wind. (Netflix is behind the documentary and will release a completed version of Welles’ movie at the same time.)

Featured image: Fred Rogers (left) with Francois Scarborough Clemmons (right) from his show Mr. Rogers Neighborhood in the film, WON’T YOU BE MY NEIGHBOR?, a Focus Features release. Credit: John Beale