How VFX Supervisor Conjured Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets

The first time Scott Stokdyk worked for Luc Besson back in 1995, the French auteur hired him to work on his then-groundbreaking sci-fi flick The Fifth Element. “At that time I was just this computer artist sitting at a work station for fourteen hours a day in a little dark cubicle excited to be working in the world of film,” says Scott. Since then, visual effects have made gargantuan advances, and so has Scott. He won an Oscar for his work on Spider-Man 2 and made munchkins for Oz The Great and Powerful.

A couple of years ago, Besson beckoned Stokdyk to Paris and unveiled his vision for sci-fi epic Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets (opening Friday.) “Luc presented me with the most amazing concept artwork I’d ever seen,” Stokdyk says. “He showed me one image after another after another until my mind was completely blown. The challenge was going to be making this world come to life.”

Concept art from Ben Mauro. Courtesy Ben Mauro.

Concept art from Ben Mauro. Courtesy Ben Mauro.

Valerian follows handsome detective Valerian (Dane DeHaan) and spunky pilot Laureline (Cara Delevinge) who encounter hundreds of intergalactic species on a mission to save pale, peace-loving Pearl aliens from extinction. Scott enlisted New Zealand’s Weta Digital, San Francisco-based Industrial Light & Magic and Montreal company Rodeo to conjure the futuristic universe with more than 2,700 VFX shots. Top priority for creature effects: pull the heartstrings. Stokdyk says, “The Pearl characters are beautiful, sort of androgynous aliens with skin that changes color with these chromatophores, like sea creatures. We wanted to make them interesting looking, but even more than that, we wanted audiences to care about them.”

Pear alien. Concept art from Ben Mauro. Courtesy Ben Mauro.

Human actors dressed in sensor-embedded motion capture suits performed “Pearl” characters against blue screen soundstages at Besson’s Cite Du Cinema, where the entire movie was filmed early last year. “Then we’d take over and turn the actors’ performances into synthetic visual effects creatures,” Stokdyk says. “We were always asking ourselves, ‘Is there anything we can do with visual effects to enhance the emotion of the scene.?'”

The answer, provided by Weta artists, focused on the eyes. “They’ve gotten very good at creating subtleties of muscle movement in the face, particularly around the eyes,” Stokdyk says. “Within the individual shots, it became about nuances: can you make the right pupil dilate? Can you make the tension of the eyelid work? Can you make the eyes start to well up with tears a little bit? Weta layered these subtle performance bits on top of the actors’ performance. We pushed the effects so audiences really care about something we created from scratch.”

Motion capture tricks also transformed Rihanna glamapod character “Bubble” from Cabaret-style stripper to sexy nurse to a shimmering blob of blue gelatin. “The first time we see Rihanna, she shows her ability to blend into all these different personae” Stokdyk says. “The second time she’s more of an amorphous, raw-looking gelatinous character. We didn’t want to do simple-looking morphs, to to make her appearances visually interesting, we had Rihanna in real costumes, and we put her in a mo-cap suit with 60 cameras going, and we also had a stand-in dancer to get motion ideas off of. We used a little bit of everything.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ogf2uuTo0LE

Besson put his own analog twist on the pre-vis process to illustrate the film’s 18-minute opening sequence, which flips back and forth between a tourist beach and the space-age “Big Market” mega-mall. The director gave video cameras to 120 students from his L’École de la Cité school and instructed them to film each of the storyboard’s 600 shots. Stokdyk says, “That whole scene is so weird and high concept. After the students shot the storyboards on video, Luc edited the whole sequence together. It was a really effective way to get all those ideas out of Luc’s head so everybody was on the same page.”

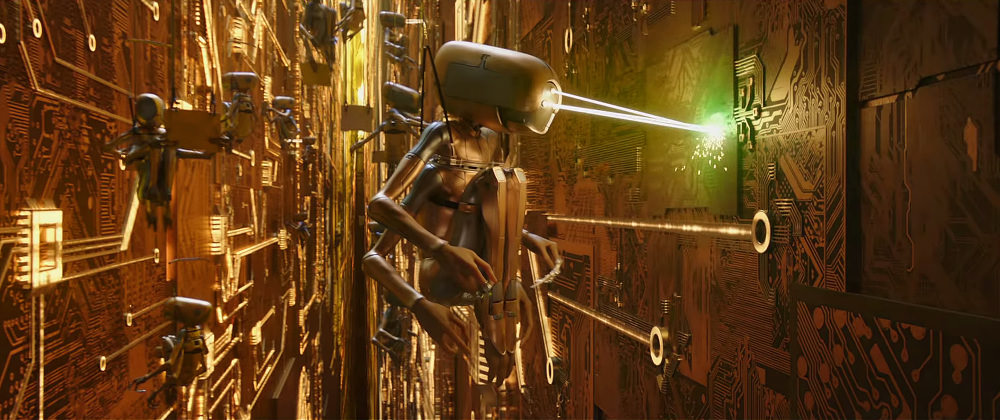

The Big Market was rendered by ILM as actors were being shot against blue screen in Paris. Stokdyk says, “We figured we could dress the scenes in post, so we gave ILM a blank canvas and they created their own crazy library of concept art, along with Ben Mauro, and basically assembled this virtual marketplace that’s probably a 100 times bigger than the biggest mall in America. As Luc put the blue screen shots together, ILM used all these different shop pieces to build the marketplace around the layout in each of the frames.”

Given the number of blue screen backdrops featured in Valerian, Stokdyk did his best to provide the live-action stars with “real” stunt performers who would later be digitally sheathed to appear as alien freaks. He says, “By and large the question you’re concerned about as a visual effects director is, does the actor have something to work against? Whenever Dane and Carla interacted with a creature, we’d try to have them play back and forth with a person in a motion capture suit. You want to avoid situations where the actor has to pretend that something’s there when he’s looking into an empty blue screen.”