Talking to Writer-Director Tobias Lindholm About his Oscar-Nominated A War

The third big-screen collaboration between Danish writer-director Tobias Lindholm and actor Pilou Asbaek, A War follows a company commander through the horrors of Afghanistan and back to Denmark, where he's put on trial for alleged war crimes. The movie, an Oscar nominee for best foreign-language film, has a semi-improvisational style and features mostly nonprofessional performers. Lindholm's two previous movies, R and A Hijacking, are equally intense: The first is a prison drama and the second about a crew held by Danish pirates. Lindholm's interview with The Credits, which has been edited for length and clarity, began with a discussion of the contrast between his harrowing films and his homeland's widely publicized status as the world's happiest country.

"I want to confront the truth of us being the happiest nation on Earth. We are at the same time one of the countries with the highest rate of suicide. So there is more to it than that. My view to make realistic films that can appreciate the complexity of the world, rather than trying to simplify it. Living in Scandinavia, we often a tendency to think that we know better than everybody else. And I'm not sure that's true. We are a very secure place, so for me it was important to show the complexity of the war. I wanted to try to bring the audience down into the boots of the soldiers."

How did you find the soldiers you cast in the film?

I met one of them at a wedding. I told him about the story, and he came to my office for a cup of coffee. He would bring fellow soldiers that he had fought with in Afghanistan. A lot of them were very willing to share their stories with me. Slowly I convinced them that they would be good actors, or at least good professional soldiers in this film.

It was a process of finding soldiers that had the experience, and witnesses of war, which I needed. That could secure the accuracy of the way we portrayed the war. Instead of a reference to other war films, we wanted to make a reference to the reality.

Dar Salim and Pilou Asbæk in A WAR, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

Had you already written the script?

I had done the outline of the basic conflict. I read an interview back in 2002 with a Danish officer going on his third tour in Afghanistan. He said, "I'm not afraid of getting killed down there. I'm afraid of getting prosecuted when I get back home because of the changing rules of engagement." That fascinated me. I did a basic structure of a story, with a guy ending up in a situation where he ordered a bombing because he wanted to save all his men. And then ending up on trial.

But all the details of this world I would add from my interviews with the witnesses, Danish soldiers, but also Afghan refugees who had escaped the war in Helmand province. And the talks I had with a judge and lawyers and prosecutors to try to understand the full logic of it.

Did you visit Afghanistan?

I was not allowed to go. We couldn't insure it. And the forward-operation bases were all emptied out. There were no Danes left out in the landscape. The Danish soldiers were now located in huge camps. There was no reason for me to go there, because I didn't want to see these huge military facilities. I wanted the story to happen in the forward-operation bases. So we decided instead to go to Turkey to locate Afghan refugees in camps there, and find a location that could represent the landscape of Helmand province.

Were there aspects of the war that veterans didn't want to talk about?

I don't know, because I don't ask that many questions. I just listen to the stories. They just tell me stuff they want to tell me. You'll find that human beings want to share their lives. We all want to do that. Slowly, the soldiers started to feel comfortable about sharing these stories. And I would take bits and pieces from each anecdote and fit it into the outline.

Do you work the same way when you write scripts for other directors?

This is me writing for me. I feel that I can allow myself to be unclear in some ways. When I'm writing a script, for example, for Thomas Vinterberg, I am writing the best possible blueprint for his film. I have to be very precise in my descriptions. When I'm the director, I allow myself to be a bit more sloppy, and a bit more live. I feel that these are two very different processes, even though both happen in my office at home late at night.

You're a late-night writer?

I have three small kids, so there's always one who's home sick with the flu or something. So when they sleep, I work.

You're working on a script for Thomas Vinterberg now. He and Lars von Trier were the framers of Dogme '95, which called for an austere mode of filmmaking. Do you see your approach as being an extension of that?

Definitely. I think that if they hadn't made a rule that guns were not allowed, this could have been a Dogme film. I was very inspired by Dogme. It opened my eyes to the Dardennes brothers, to John Cassavetes, to what happened in the '60s in France. I am proudly on the shoulders of those guys who made the first three or four Dogme films.

Luckily, I am working with Thomas. I'm not educated as a director. I'm educated as a screenwriter. So I've learned a lot from him, and I've talked a lot to him about how to build the machinery to direct a film.

Your lead actor, Pilou Asbaek, has said, "the one thing that Tobias hates is acting."

He calls it acting. I call it lying. When he's not being honest, when there's no connection between the emotions that you represent and the emotions that you express. I don't want him to act. I want him to react. I want him to be present right there in the situation. Because of that, I need to surprise him once in a while. I need to make him not too comfortable in the situation. Luckily, he's extremely good at making himself available for whatever happens.

Pairing him with real veterans and refugees put him in a situation where he cannot just wait for his moment to say his line. He needs to be alert all the time, and that's what we're looking for.

Pilou Asbæk in A WAR, a Magnolia Pictures release. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

This is a technique you use not only with professional actors, but also with people who are not trained performers.

Yes, definitely. I feel that nobody in real life knows what's going to happen around the next corner. So I see no reason for people in films to know it. It seems to me that often viewers can detect that, and can feel it.

It's the same reason we don't give the audience a greater view of the battle scene. We're just staying behind the wall with the soldiers. Because if we put the camera up there, the cinematographer would get shot — if we believe in the reality that we're creating. If we gave the audience the idea that the camera can be up here, it's just the soldiers that can't, we've already told them that it's not really dangerous.

For this film, you used that technique with children, and with actual Afghan refugees. Do you ever feel you've pushed them too far?

The day we did the scene where the Afghan family comes to the outpost, asking if they can stay there, that was probably the hardest day I ever had shooting. This family was not trained to act. So after a couple of hours of shooting, everybody started to forget that it wasn't real. And the emotions, at least, were real for them. I found it challenging to control that situation. Especially with the man and the wife, we could see they were reminded of stuff that they wanted to forget. That was hard.

With the kids at home, I decided never to really write any lines for them. I would just let them be kids, A teacher in film school once told me, "Never work with animals or kids. It's too hard." But I realized it's only hard if you want them to be anything else but kids or animals. Kids can be kids. So we just rented a house and said, "When we're filming, this is your home." We bought a lot of toys and stuff that they liked and that they had at their own home, and they just went in and lived the life of this pretend family. And they were pretty good at that.

In the hospital scene with Andreas, the young kid who's crying, he's crying for real. But the thing we did was, he would cry for 30 seconds every morning when his father left the set to go to work. This particular day, I asked his father to stay around until we were ready to shoot. So Andreas would cry and say, "Where's my father?" In that one take. But all the other takes we have, he's laughing and finding everything funny. So we only had 30 seconds that worked from that day.

That makes things easier in the editing room.

Exactly! [laughs]

You shoot long takes so people will forget that the camera. Is that method influenced by documentary?

It definitely is. I try to find the logic in documentary. What kind of agreement we have between the character and the camera. What is it in a documentary that makes the camera so alert? And what makes the character so alert? Of course, we have scenes with information that I need to convey because there's a story to tell. But I love to follow the script in the first two or three takes, and then let go and see what happens in the next ones. Once in a while, we'll film for an hour, an hour and half. We shoot digitally, so we can do that. I often regret it when I'm the editing room. To watch all this material! But there's always some magical bits and pieces, where it suddenly seems very real.

You've said that your collaborators are like a small rock band. Is it important to work with the same people again and again?

I feel that I don't have a career; I have a life. And I definitely want to spend my life with friends. When I'm leaving my kids and my wife to go shoot a film, at least I'm spending time with people that I care about. I'm a team player. I used to play soccer when I was younger, and I still feel very close to all these guys who are bringing the best they have. I need us to be more than a film crew. I need us to connect on a human level as well.

We're entering spoiler territory here, but you wrote two endings for the film. Did you shoot them both?

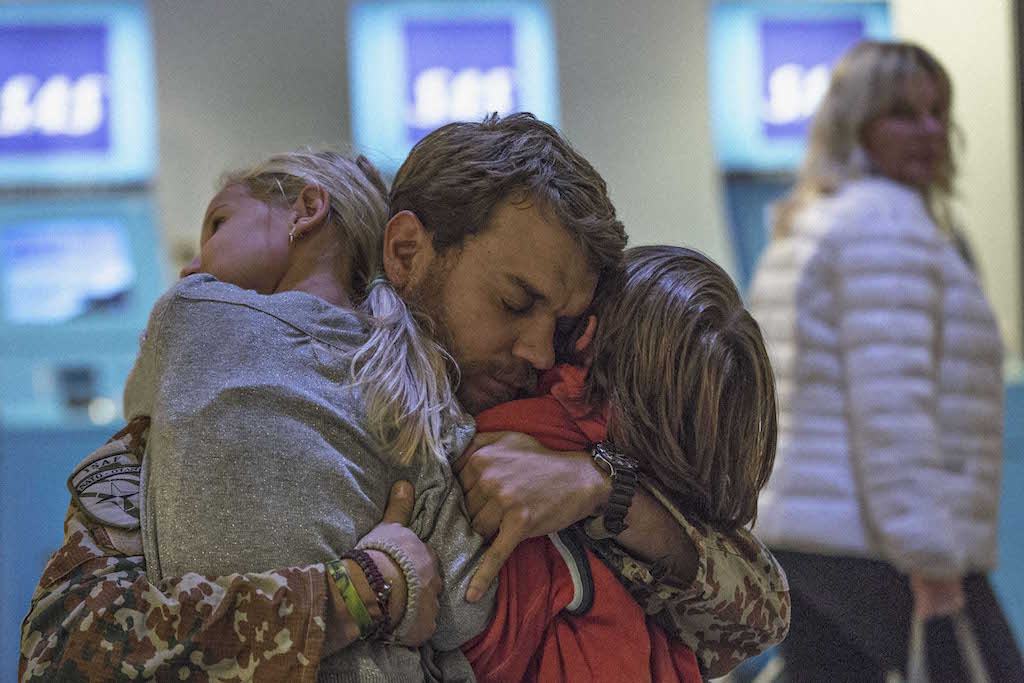

I did. We shot an ending where we would send him to jail for six years. I never gave Pilou the last five pages. So he didn't know what was going to happen. Neither did the actress who plays his wife. I kept them in the dark because I wanted to make a story that could work with either ending. My wish was to make the film we've done, with this ending. But I knew that if we sent him to jail, at least we have a tragedy with a guy who's lost everything. And that will have an emotional effect on the audience. But I definitely was aiming for this ending, where we see that imprisonment is within him, not just outside him. I didn't want to make a victim of him. I wanted to make it more complex.

How did you know that the ending that you chose was the right one?

We tested stuff in the editing room, and when we had done the first cut, and the ending was there, I never looked back. I feel the ending leaves him in a place where Denmark as a nation is right now. In the darkness, wondering about what actually happened.