Cinematograopher Goes Dark With The 33 Miner Drama

Cinematographer Checco Varese understands terror. After all, he shot horror maestro Guillermo del Toro's vampire series The Strain and in his earlier years, the Peruvian-born director of photography filmed war zone documentaries. But nothing prepared Varese for the pitch-black adventures in underground filming he encountered while making miner drama The 33. Inspired by the 2010 ordeal in which 33 Chilean miners spent 69 days trapped 2,600 feet beneath the earth, the movie stars Antonio Banderas, Lou Diamond Phillips and Juliette Binoche in a gripping recreation of the disaster.

Before shooting began in Columbian, which doubled as location for the Chilean mines, Varese wrapped his head around the dark heart of the story by spending time alone in the abandoned Zipaquirá mine. "They drove me for two miles in a golf cart-type thing all the way inside this mine," Varese recalls. "It was like going into the belly of Lucifer. I told the guys to come back in an hour and walked around with my light meter taking some measurements. Half an hour later I decided to turn off my flashlight and man, that was the most horrifying 15 minutes of my life. You don't see anything, you hear your own heartbeat, the flow of the your blood stream — with every deep breath comes more anxiety as you hear the rock shifting. The question for me became, 'How do you convey that sense of darkness in a movie where you have to see the actors' faces?"

To address that challenge in The 33, directed by his wife Patricia Riggen, Varese tried mounting lights on the side of the cave by drilling holes into solid rock and hanging lamps on sticks of rebar. That proved unwieldy. Then Varese instructed the actors to light their own scenes using lights mounted on their miner helmets. "For example, I'd tell Lou Diamond Phillips and Antonio Banderas, 'When you talk to each other in the scene, you cannot look each other directly because you'll be shining the light from your helmet right into the other guy's face. You need to tilt it down a little bit and point the light at his chest." Varese, who operated one of the production's two Arri Alexa digital cameras himself, choreographed each performance. He explains, "The actors rehearsed first with Patricia, and then I'd go through the scene to make sure the actors were lighting themselves correctly."

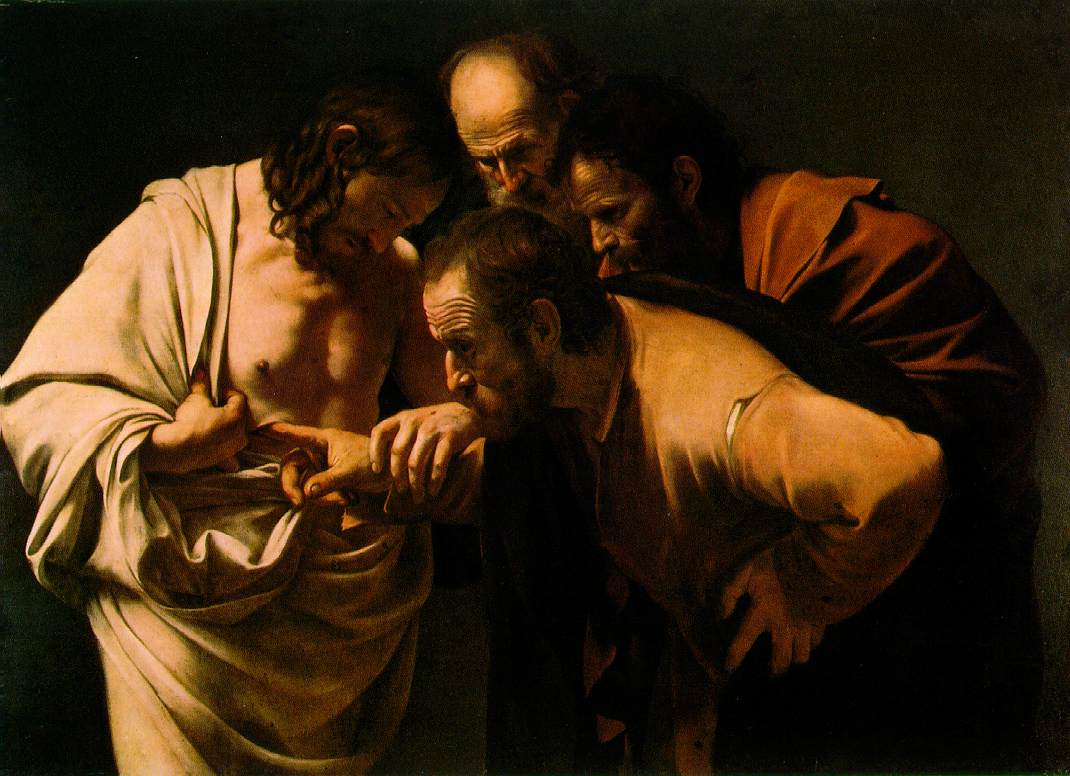

A Painterly Influence

The 33's evocative underground tableaux share a brooding aesthetic with one of Varese's favorite painters, 16th century Italian artist Caravaggio. "I watched a few horror movies to see how they handle lack of light, but that didn't work for my purposes," Varese says. "Then I looked at Goya, but he painted tragic, depressing demons. That just wasn't right for The 33 because there's suffering, yes, but it's also about human solidarity and faith and passion for life. So one night I woke up at three in the morning and realized 'Caravaggio!' He paints these suffering male characters, whether its Christ or a saint being tortured, but they're still beautiful."

Like Varese, Caravaggio relied on a single light source to illuminate the foreground figures against a black background, "It's not that I tried to copy Caravaggio, but I was inspired by his work in the way I shot The 33. It's dark, these miners are hungry, but there's also a real need for beauty so I could show these miners as human beings."

Usings limited light sources, Varese helped re-create the miners' plight in 'The 33.' Courtesy Warner Bros. Pictures.

Dust, Soot, Sand

Varese describes The 33 as "The hardest movie I've ever made." Living in shipping containers modified to serve as trailers, cast and crew filmed underground for 31 days, 14 hours a day with no cell phone or walkie talkie connection to the outside world. "It was like we were all in a submarine," he says.

And then there was the dust. Varese says, "A week and a half after finishing the movie, I remember taking a shower and the towel turned black. Even now, sometimes I'll put my hands in the pockets of jacket I wore during the shoot and they're full of sand and dust and soot from the mine."

Making "Camp Hope" Shine

While Varese kept Technocrane-mounted camera movement to a minimum for the understated underground scenes, he and Steadicam operator Matías Mesa used hand-held cameras to film antic ground sequences at the "Camp Hope" site. Teeming with family members, news crews and rescue teams, the scenes were shot in Chile's Atacama Desert, a few miles from the real-life disaster site. "Above ground, the clock's ticking because you need to find these men, then feed them, then rescue them because if you don't, this huge rock is going to fall on top of their heads. We captured that feeling through a very passionate, yet not frantic hand-held cameras."

An Unplanned Epilogue

Once the filmmakers completed the scripted drama, they gathered the actual miners for a picnic on a beach near Santiago, Chile. Varese filmed individual portraits in black and white, packed up his gear and almost missed out on what would become the movie's unplanned grand finale. "The miners asked Patricia, 'Are we done with the filming?' and she said 'Yes.' Then all 33 miners got into a circle and hugged. Patricia started screaming at me, 'Get the camera, get the camera, where are you going?' I was like 'Whoa, hold on a second!' I found the camera, turned it on, steadied it as much as I could and shot the last scene in the movie."

Varese was thrilled to bear witness to the unscripted survivors' reunion. "Seeing who the real miners are — to me that's one of the most poignant moments in the movie," he says. "When I shot these guys being together, being brothers, the sun was perfect in the sky. I'd have to say luck was on my side."