With NASA’s Help, The Martian Plumbs Real Science for Thrills

As a genre, science fiction tends to lean more heavily on the fiction side of things than the science. Think Star Wars, The Matrix, and Blade Runner. Ridley Scott’s latest movie The Martian, on the other hand, is an ode to the compelling nature of actual science, with both a plausible plot and realistic aesthetics. Based on the best-selling novel by computer-programmer-turned-author Andy Weir, The Martian tracks an ill-fated manned mission to Mars when astronaut Mark Watney (played by Matt Damon) is left stranded alone on the red planet, with only his wits and botany knowledge to keep him alive. Meanwhile, back on Earth, the world is transfixed by ‘the Martian’s’ plight, as NASA formulates a plan to bring him home.

Part of the reason the film is rooted quite firmly in reality, is that the story is set in the not too distant future, around 12 to 15 years ahead, and the scientific aspects of the book are backed up by current theory. The major exception being the sandstorm that derails the mission, leaving Watney stranded.

“I needed a way to force the astronauts off the planet, so I allowed myself some leeway,” Weir says in the production notes. “Plus, I thought the storm would be pretty cool.”

The author explained in an NPR interview why a fierce sandstorm can’t occur on Mars:

“In reality, Mars' atmosphere is 1/200th the density of Earth's. So while they do get 150 km/hr sandstorms, the inertia behind them — because their air is so thin — it would feel like a gentle breeze on Earth. A Martian sandstorm can't do any damage. And I knew that at the time I wrote it.”

He then went on to outline why he rejected more scientifically accurate alternatives:

“I had an alternate beginning in mind where they're doing an engine test on their ascent vehicle, and there's an explosion and that causes all the problems. But it just wasn't as interesting and it wasn't as cool. And it's a man-versus-nature story. I wanted nature to get the first punch.

“So I went ahead and made that deliberate concession to reality, figuring, 'Ah, not that many people will know it.' And then now that the movie's come out, all the experts are saying, 'Hey, everyone should be aware that this sandstorm thing doesn't really work and Mars isn't like that.'

“So I have inadvertently educated the public about Martian sandstorms. And I feel pretty good about that.”

Rogue fantastical sandstorms aside, in the spirit of the accuracy and attention to detail of the rest of Weir’s novel, the producers and Ridley Scott requested that NASA come onboard as a consultant on the production from the beginning. In the real world, NASA is steadily working towards their stated goal of sending humans to Mars in the 2030s. Production was allowed to film rocket launches at Cape Canaveral, including the including the December 2014 liftoff of the Orion, a cutting edge spacecraft designed to take humans to an asteroid in 2025. Its successful launch was a crucial step towards future human missions to Mars.

To help bring the NASA headquarters of the future to life, Dr. James Green, NASA's Director of Planetary Sciences, gave production designer Arthur Max an extensive tour of Houston’s Space Center. Max also viewed the old Mercury and Apollo mission control centers, as well as the current Center, which handled the Space Shuttle missions and tracks the International Space Station.

“I combined some of the elements we saw at NASA and then pushed out into the future with the design – what we think their next control room may look like,” says Max. “NASA was remarkably helpful in not only giving us great resources and input, but approving all of our designs.”

In Weir’s book, the spacecraft Hermes takes the Ares III crew on their nine-month journey to Mars. For the production, the Hermes was constructed on Stages 2 and 3 at Budapest’s Korda Studios (the Martian landscape was also recreated there). Unlike, say, Star Wars’ iconic Millennium Falcon, which was inspired by George Lucas’ half-eaten hamburger, the Hermes spacecraft technology is based on NASA’s advanced design plans. It’s powered by a nuclear powered ion plasma propulsion engine, which Max says has yet to be depicted in a movie because the technology is so new. The design incorporates a large telescopic arm that places the heat-emitting reactor a safe distance from the ship.

“We’ve tried to stay close to practical reality and cutting-edge technology while creating an eye-catching aesthetic,” he says.

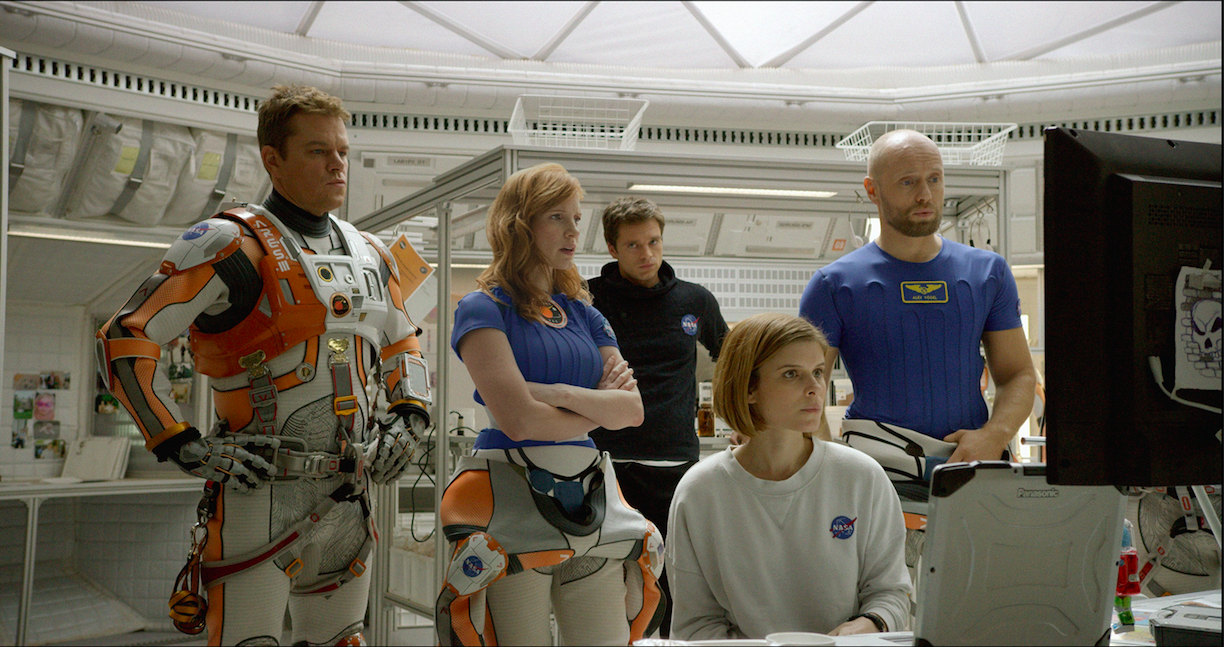

Costume designer Janty Yates followed a similar edict when designing the crew’s spacesuits. As with the other elements of the production, Yates’ wanted the suits to fall in line with the real future of spacesuit design, while looking good on film and keeping in mind the practicalities of moviemaking. Yates met with a curator of the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C., which houses a collection of spacesuits dating back to the beginnings of the Mercury program, America’s first human space flight program, which ran from 1959 to 1963, and conducted research at Johnson Space Center and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“I saw the rovers, I saw them building satellites…It felt like I was already in a science fiction film,” Yates says.

“They sent me so many images that were incredibly useful. We saw the designs of the suits that they are planning for missions extending beyond even 2030.

“From the start, Ridley said he wanted the surface suits to be slender and allow for movement, yet still offer a nice silhouette. NASA’s suits have the helmet built in, which wouldn’t work for our purposes, so we had to change that design. We also needed to make some changes for aesthetics and practical needs of filming, and I think we hit the mark between function and form.”

Marrying NASA's expertise to the filmmaking team Scott put together, The Martian promises to be the best of both science and fiction.