The Real Science Behind Matt Damon’s Troubles in The Martian

In Ridley Scott’s new film The Martian, Matt Damon plays Mark Watney, an astronaut who is marooned on Mars after a brutal storm separates him from the rest of his crew. (This is the second film in two years that has seen Damon marooned on a hostile planet—it happened to him in 2014's Interstellar). He is presumed dead, considering the soonest his comrades could possibly return to save him is in four years, and he’s at a station that can only support human life for 31 days. As Damon’s character says, the only way he can possibly survive is to “science the sh*t out of this.”

Sending a manned mission to the Red Planet is NASA's most ambitious goal. In President Obama's January State of the Union, he had this to say: "Pushing out into the solar system not just to visit, but to stay. Last month, we launched a new spacecraft as part of a reenergized space program that will send American astronauts to Mars. And in two months, to prepare us for those missions, Scott Kelly will begin a year-long stay in space. So good luck, Captain. Make sure to Instagram it. We’re proud of you."

Scott Kelly's year-long stay at the International Space Station is part of NASA's research into figuring out how to prepare a human being for the three-year journey to Mars. The physiological and psychological toll extended time in space has on a human being wasn't always a major concern for the agency. Astronauts of the John Glenn and Neil Armstrong era were stoics, and it wasn't until many years later that NASA began to pay serious attention to the toll space travel has on astronauts. In fact, one historic case of a treacherous journey that lead to isolation, near starvation and madness, one not dissimilar to The Martian's plot, has been a major research subject for NASA. Only this journey wasn't into space.

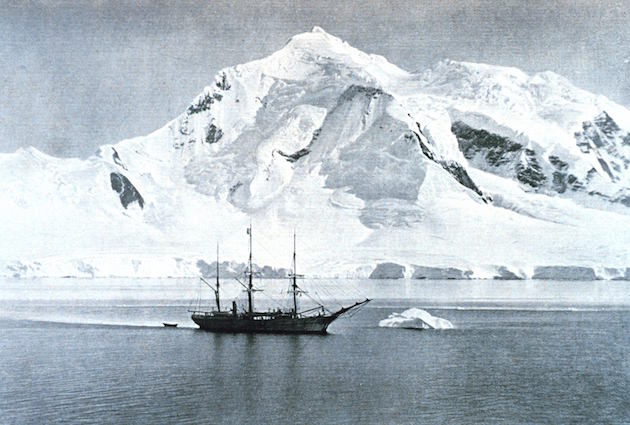

As Tom Kizzia of The New Yorker reported in his April 20th piece “Moving to Mars,” about a group of NASA recruits who are being studied in a massive, months-long Mars training simulation, NASA's research efforts into what can happen to the human body and mind during prolonged periods of isolation and physical degradation began with the records from a 19th century seal-hunting ship. NASA research consultant Jack Stuster began examining the records of the Belgica, which was caught in the pack ice of the Bellingshausen Sea in the March of 1898 and had to settle in for the winter in Antarctica. Along with the seal hunters, the ship also had a scientific expedition on board with an international crew. The crew had planned for the Belgica to spend their winter in warmer latitudes, and so were not prepared with proper food or clothing for a long stay in the ice. “No ship had ever spent a winter locked in the Antarctic ice,” Kizzia writes.

What happened next has been the focus of intense study by NASA, as it offers insight into the effect isolation, cramped quarters and the grinding sameness that traveling to the red planet would require. Shooting astronauts that deep into space, a hundred million miles from home, out of close contact with mission control (the lag time between outbound and inbound messages on a voyage to Mars would mean no communication in real time), would be a lot more like the experience for the crew aboard the Belgica than one might first suspect. Yet the experiences reported aboard the Belgica are even closer to The Martian than just the similarity of human beings caught in a hostile environment: the ship's crew, specifically two men, had to "science the sh*t" out of their situation to survive.

“An eerie despondency settled over officers and crew as the days grew short and ice groaned against the hull,” Kizzia writes. They were low on essentials, like proper winter gear and coal. They stopped talking to each other, and the dinners of tinned meat became sources of frustration and anger. Then the men started to lose it. A young Belgian geophysicist died, and was buried through a hole in the ice. Paranoia set in, with one crew member becoming convinced the others were trying to kill him. Another tried leaving the ship so he could "walk home to Belgium." The ship’s cat even grew despondent and died. An American doctor by the name of Frederick A. Cook on board wrote that, “We are at this moment as tired of each other’s company as we are of the cold monotony of the black night and of the unpalatable sameness of our food.”

Eventually, Cook would prove heroic, and his exploits on the Belgica would provide NASA with a blueprint on how to keep men alive in hostile environments. With help from the ship’s first mate, a Norwegian named Roald Amundsen, Cook began improve the crew’s morale and fitness with a regimen of exercise, improvised medical treatments, a crucial new source of protein, and even the deployment of some much needed entertainment. Cook had the men take walks around the ship to keep them in shape (they called it "madhouse promenade"). For men with the weakest heartbeats and lowest morale, he sat them by the warmth of the ship’s coal stove. He had the men start eating penguins, which were vitamin-rich, roasting them in blood and cod-liver oil. Finally, Cook organized various entertainments, including a beauty contest among illustrations he tore from magazines. Once summer returned, Cook and Amundsen had gotten the men into okay enough shape that they were able to saw a channel to open water.

Once NASA began researching the Belgica’s mishap in Antarctica, they began putting more effort into studying the stress of space travel, which, as mentioned before, had never been a big priority to the program or the astronauts themselves. Jack Stuster has now studied many voyages of discovery, including the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria (which Kizzia notes anticipated NASA’s principle of “triple redundancy”), finding that crews united by a spirit of discovery excelled. He looked at a three-year journey into the Arctic led by the Norwegian Fritjof Nansen, which was planned superbly, including a high level of scrutiny into selecting the crew. Attention to things like crew compatibility and habitat design, he found, are crucial.

Today, NASA is putting astronauts through “high-fidelity mission simulations” in environments on Earth that as closely match Mars as possible. One of these missions is taking place halfway up Hawaii’s Mauna Loa volcano, where the slow-oozing shield volcano is, like Mars, a bleak landscape that looks surprisingly similar to the images NASA’s robotic rovers have sent back from the planet.

On the volcano, NASA’s six crew members live in a 1200-square-foot dome. Water is heavily rationed (each person can shower for a total of eight minutes a week), communication with mission control is delayed by 20-minutes each way, and each crew member is engaged in personal research projects, as well as crew projects, while they themselves are studied.

NASA is testing group dynamics and morale in an effort to design systems that will be able to send a team deep into space. These efforts aren't to keep an astronaut from being marooned on Mars, but rather to keep them sane enough, and healthy enough, to make it to Mars and back. As entertaining as The Martian looks, if NASA stays the course and the next few presidents keep the mission funded, we might actually see an astronaut on the Red Planet, and hopefully in good shape and good spirits, in the not too distant future.