Brett Morgen on Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck & how Frances Bean Made it Happen

Nearly eight years after director Brett Morgen (The Kids Stays in the Picture) was approached by Courtney Love to make a film about her late husband’s life, the documentary, Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, is finally available to fans around the world — premiering on HBO and in select theaters tonight, May 4th.

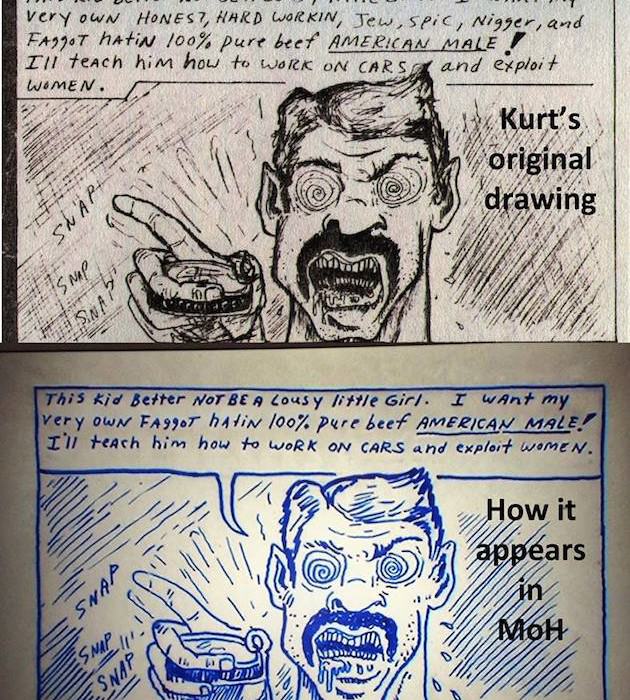

Using never-before-seen and heard artwork, personal writings, music and home movies (it’s amazing how much footage there is of young Kurt), Morgen paints a picture of the complete, definitive Kurt — one who is more multifaceted artist than rock icon who took his own life in April 1994.

“The film would not exist today without Frances (Bean Cobain),” Morgen says, citing that it was Kurt and Courtney’s now-22-year-old daughter who was the reason so many people agreed to be interviewed, including Kurt’s mother, father, and sister.

We spoke to Morgen, dubbed the “mad scientist” of documentary film by the New York Times, about his monumental film.

How did you become involved with this film originally?

I got a call from Courtney Love in 2007. She had seen my film, The Kids Stays in the Picture and wanted to explore the idea of making a film about Kurt. While there’s been a lot written about Kurt over the years, and a couple of attempts to bring his story to the screen, Courtney was sitting on a treasure chest of art that Kurt had produced during his lifetime, and I think she came to me because of the way I had dealt with the Bob Evans film. Once I was granted access to that material, I knew that we had the makings of something truly unique.

How would you describe it?

It’s an unorthodox movie in that it’s probably best described as an interior journey through Kurt’s life. Generally that’s maybe something you try to provide in fiction or an autobiography, but to do a documentary about someone’s inner journey is a bit challenging. However, with Kurt, he had left behind such an immense library of art, both visual and aural, and he was so expressive with his art, that in a sense, he left behind this sort of organic visual and aural autobiography of his own experiences through his life. And because he worked in so many different forms of media, I find it to be one of the most complete visual and aural autobiographies of anyone in my generation.

Was anything in the archives off-limits?

No, nothing. Courtney didn’t see the film until two days before the premiere and Frances was the first member of her family to see it, and I never received a single note or comment. It was important both for the fans and myself that I was afforded final cut on the film, because one of the thoughts I had was that no matter what the film was going to be, it needed to be honest. We had no intentions of ever going into the final weeks of Kurt’s life. This was a movie about Kurt’s art and his journey, and for the fans and people who really appreciated Kurt, it’s almost like opening up a candy box of these nuggets of Cobain. While it’s hard enough to ever fully understand yourself, let alone another person, Montage of Heck will probably get as close as we can because the movie’s all built upon primary sources — none of which I doubt will ever be available again.

How involved was Frances?

The film would not exist today without Frances. She was the reason people were giving us access to their archives, and why they agreed to be interviewed, and why they agreed to participate in the film. She set the agenda for me in our first meeting and made it very clear what she was hoping to get from the film, and then she signed off on the version I presented to her in October. She likes to underplay her involvement, and I get that, because it’s not like she was dealing with the day-to-day making of the film, because that’s not what she does, and that’s not how I operate. But without Frances, this film does not exist.

You’ve said that you wanted to create a film that gave her a couple of hours with her dad, which is a really powerful sentiment.

When I first met Frances, we were shaking hands, and she held my hand and said, “You know, I’m just meeting you now, and I already know you more than I know Kurt, because I have no memories of him.” You know, you don’t really remember anything before you’re two. Shortly thereafter, I went to the storage facility where Kurt’s materials were housed with Frances, and it was incredibly intense for both of us, and I saw her sort of discovering her father in a manner she hadn’t before. At that point, my entire focus shifted. I genuinely wanted to give her the experience of a couple hours with her dad. And then upon seeing the final cut, we embraced, and she whispered, “Thank you for giving me two hours with my dad.” I doubt I’ll ever achieve anything as satisfying through my work as that.

Were you a big Nirvana fan?

I was a casual fan. I’d seen them play a couple of times, and culturally they came up at the same time, so Nirvana has a tremendous impact on my life from a cultural standpoint, But once again, I was approached by them–it wasn’t some lifelong dream to do a film about Kurt.

Obviously it’s gotten a lot of critical acclaim, but how have audiences reacted so far?

It’s almost like meeting an old friend for the first time. You sort of go, ‘Oh that’s who he is,” and it’s over. And you sort of realize there’s not gonna be anything else. And that’s sort of the punch to the gut. Yet at the same time, I see people not so much in tears by the end, but appreciative of the time they got to spend with Kurt. It’s an interesting situation. The film has been very well received, and people come up to me like, “Dude, you must be so psyched.” But it doesn’t feel celebratory, and it doesn’t feel like anything to be giddy about. It feels rewarding in that the team I assembled and myself put everything we had into making this film as best we could. It’s incredibly satisfying to see that people are experiencing it in the manner we intended, but the reality is, Kurt’s not here, and obviously we would all wish that we didn’t have to make this film.

Featured image: Kurt Cobain as a teenager on the guitar. Courtesy HBO Films.