Talking Risks & Rewards With Birdman Director Alejandro G. Iñárritu

Alejandro G. Iñárritu's first crack at directing was 2000’s Amores Perros, a complexly woven narrative surrounding three separate stories all connected by a single car accident. The film earned wide acclaim and an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film, and the Ariel Award for Best Picture from the Mexican Academy of Film. It put the former composer and first time director on the map.

It also was the first film in his “Trilogy of Death,” and was followed by 21 Grams (2003), which loosely followed the structure of Perros, interweaving several storylines around the consequences of a tragic car accident. 21 Grams’ characters include a critically ill mathematician (Sean Penn), a grieving mother (Naomi Watts) and a born-again ex-con (Benicio del Toro) whose faith is severely tested by the accident and its aftermath. It's not light viewing, and it's weighty themes and major performances were born of Iñárritu's major ambition.

The final installment in the trilogy was Babel (2006), which took Iñárritu’s love of interconnected storylines global, with the film set in Morocco, Japan, Mexico and the United States. Like 21 Grams before it, Babel is non-linear, showing moments from the lives of characters that also happen to fall on the same latitude, with each storyline taking place 120 degrees apart. Four different families are all connected to one tragic accident that befalls a married couple on vacation in the Moroccan desert (Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett). It won the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture, and was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. In a little more than six years, Iñárritu's "Trilogy of Death" had made him a major director.

His next film was Biutiful (2010), about Uxbal (Javier Bardem), a Spanish man who lives in Barcelona and has the ability to talk to the dead. Uxbal makes his living finding work for illegal immigrants, while looking after his two young children whose mother is an alcoholic and bi-polar. Uxbal's diagnosed with terminal prostate cancer, and his coming death begins to guide his every move as he negotiates all the lives he feels responsible for. The film was nominated for two Academy Awards: Best Foreign Language Film and Best Actor for Bardem, the first time in the Academy’s history a performance entirely in Spanish was nominated for the award.

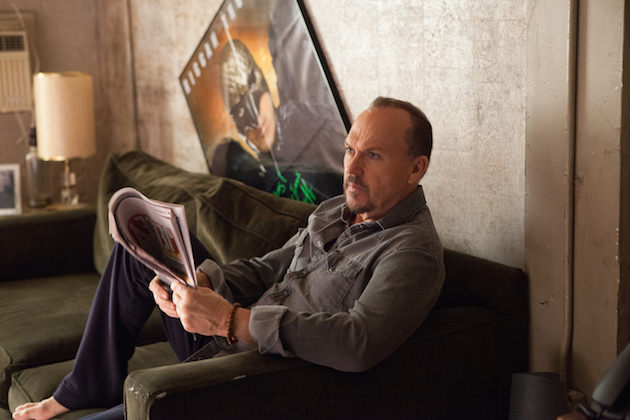

Four heavy, ambitious films. So why was Iñárritu’s fifth film, perhaps 2014’s most ambitious film, Birdman, still so unexpected? Perhaps because it was a comedy, and it centered around a bravura performance by Michael Keaton, playing a washed up actor best known for donning a bird suit in a series of superhero movies. And perhaps because it was less obviously about Iñárritu’s favorite thematic elements thus far; death, guilt, human connection (and disconnection) and love. And finally, perhaps it has most to do with the film’s now famous style, shot in what seems to be (but isn’t) a single, continuous cut, the camera rushing after and past our major characters and swooping over rooftops and through windows. Iñárritu made the most of his cinematographer, the incomparable Emmanuel Lubezki, and since it first played at this past year's Venice Film Festival, it has left audiences laughing and gasping. (Watch Variety’s video of how the film was made to look like a single seamless shot here.)

Yet upon closer inspection, the riotous Birdman, centered on Riggan Thomson (Keaton) and his attempt to mount a Broadway adaptation of Raymond Carver’s short story “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” still looks deeply at the human condition. Birdman doesn’t flinch at exploring guilt, fear, failure, and disconnection. In fact, beneath Birdman’s visual splendor and kinetic performances from Keaton, Ed Norton, Naomi Watts, Andrea Riseborough, Emma Stone and Zach Galifianakis is a film about the things we tell ourselves to get through another day, including the lies about our importance and the impossible demands we make upon ourselves. We spoke to Iñárritu about how he managed to pull off what amounted to his most ambitious project yet.

What was the day-to-day like for you on set, considering the high degree of difficulty you set up for yourself?

Every day, I became the character of the film, I became Riggan. It was a meta reality every day. It was a real creative journey toward the unknown, and that was the fun part of it, too. Honestly, it felt like what art should be, when you’re kid and you play with things, you don’t know what you’re doing but you have fun and something nice comes from it. I had a goal, but I wasn’t sure how to do it, so I was discovering lessons every day.

Without allowing yourself the luxury, many would say the necessity, of fixing things in post production, how did you get what you needed from each day’s shoot?

All of the sequences we shot were challenging because I knew each of them were part of the puzzle, and none of them could be removed or edited. Every piece, every day, was a hugely successful moment. There were ones that were more satisfying because they leaned towards the complexity or technicality that it implies. Honestly, I found myself completely nerve wracked.

There were sequences that seem to suggest you had the camera on a dolly that could somehow move through walls. How'd you get the camera over the roof, down the side of the building and then through a lower window?

Well, I would prefer to keep the rabbit in the hat.

Fair enough. Where did Riggan Thomson’s story come from? At first glance it would appear you wrote the film specifically for Michael Keaton, considering like Thomson he, too, once played a major superhero character.

I think I was interested in exploring a theme that, honestly, is related to me on a personal level, but still also related to everybody I know. It’s this voice we all have in our heads, that in a way can become this very annoying, dictatorial and demanding voice asking for more than we’re capable of, or, that we should try. And sometimes those ambitions are in disparity with our capacity, so when we confront our own limitations or mediocrity, our ego gets hurt and the vision of our world changes. It’s a very difficult relationship. You’re in a very insane battle with an intellectual notion with reality. I thought about how me, you, my mom, the dentist, everybody has that voice, no matter what, and I thought it was a very interesting thing to explore, so I chose the actor to have that battle.

And so the Raymond Carver adaptation is way beyond Riggan?

Yeah, the reason I choose Raymond Carver, not only because I’m a big fan, is I think he’s so great, and his short stories are very difficult to adapt, almost impossible to adapt for the theater. I thought it was a perfect bad idea to try that, an artistic suicide. Riggan’s got huge, pretentious ambitions, but he hits the wall with the reality of his talent, to get close to a genius like Carver.

We got the opportunity to speak with Antonio Sanchez, your drummer and composer. When did the idea to use drums as a way of getting in and out of scenes come to you?

Yeah, basically I had the idea since the moment I was writing the script, I thought the drums would become the heartbeat of each of those characters and would help find the rhythm and the flow of the film, and to keep propelling the narrative, especially considering we wouldn’t be able to rely on editing, so the drums would help that.

How much of what we see on the screen was in the script?

There was a huge amount of rehearsal and we meticulously designed every shot and every performance. Very little room for improvisation.

All of your actors really seemed to be going for it, pushing themselves as much as you and the crew pushed yourselves. Let’s start with your feelings on Michael Keaton’s performance.

I think what I really like and feel proud about, since I was writing this, there was no precedent about it. I was trying to push my own boundaries and limitations, I was a little bored and I was trying to do something with an extremely high potential for failure.We took a risk, all of us, and it required a lot of mutual trust to navigate this and get to the other side. Every time you do something without precedent, it’s scary. What I really liked about Michael is we both trusted each other, and because of that it was an easy decision to do this, he was risking exposure on many levels, and the reward is people really connected to it. It made it worth it to take that risk, because you have to defend the right to fail.

‘Defend the right to fail’ sounds like a good motto. Did you find that the actors were charged up by the challenge?

I think when you do something that is different from what you’ve done, you are on a journey, and a journey is defined by the unknown. And when you’re in the unknown, you have fun. It can be scary, but it’s a real ride. When you do a conventional film, you know where you are, where your boundaries, in a way it’s a job. But this had that childish sense of playing with materials and that possibility of failing. Suddenly it’s new, it’s a rejuvenation kind of sensation. When you don’t know if you can do it, everything becomes more alive. It’s like a live performance, and nothing compares to playing live.

Keaton’s getting a lot of deserved attention, but the female performances were outstanding as well, like Naomi Watts’s role…

One of the best actresses out there, and what she did was fantastic, I’m as proud of her as I was of any of the other actresses and actors. Emma, Andrea, Edward, all of them really nailed. They went at it deeply and profoundly in all that they did. Regardless of the recognition, for someone like Naomi…her performance is up there on the screen her for all to see.

Speaking of which, how do you feel now that all the awards are piling up?

First of all it’s funny because this kind of meta reality, the film talks about all of this award stuff in a funny way. In the bottom of my heart, I’m very thankful people have connected with it. I’ve received an incredible amount of affection, people have been really happy the film exists and it makes me very happy. I always take nominations with a grain of salt, because you go from a nominee to a loser very easily. The bottom line is yes I’m thankful, and glad.

Would you do something like this again?

My approach to cinema really changed doing Birdman, and what I learned I’ll try to apply to certain degree moving forward. Obviously, every film is different. Narratively, I always do what is best for each film that I do. I honestly can’t see cinema the same way after Birdman, though.

Can you talk about what you’re shooting now?

I’m shooting in Alberta, Canada, and some parts in D.C., it’s called The Revenant, it’s an early 19th century film, survival film, adventure film, and it’s a very different film from what I’ve done in my life, extremely challenging and intense. We’ve got a great cast of actors, but we’re in very intense weather conditions, it’s challenging at every level. But I did it because I’ve never done it before, and I want to be challenged by difficult conditions, I want to be exploring. I‘m having a lot of fun. I’m suffering, but having fun.