The Imitation Game’s Production Designer Maria Djurkovich – Part II

Yesterday we published Part I of our conversation with production designer Maria Djurkovich, whose work on The Imitation Game would have made its’ genius subject, Alan Turing, proud. Benedict Cumberbatch's phenomenal turn as Turing has understandably garnered much of the press, but if you were to look closely at every frame of the film (and, preferably, be able to pause it), you would begin to see how Djurkovich put in a superstar performance herself, planting her own codes all over the screen. In Part II, we follow the clues Djorkovich laid out throughout the film.

Djurkovich’s first tool for creating the world of the film we all see (and most of which we take for granted), is research. “What I love about my job is that on every film, you find yourself delving into a completely different world, immersing yourself in something you may know something about, or, you might know nothing about. I love the research that comes with discovering a whole world, a certain period in time, and finding the visual identity of that world."

The catch is that this deep dive into the research must be done very, very quickly. "We work at an unbelievable pace, and when you think about it, you're just given black words on white pages, and in ten, or twelve, or fourteen weeks, if you’re lucky, you have to turn all those words, all those descriptions of interiors and exteriors, into individual spaces, which on average is about eighty different spaces per film.”

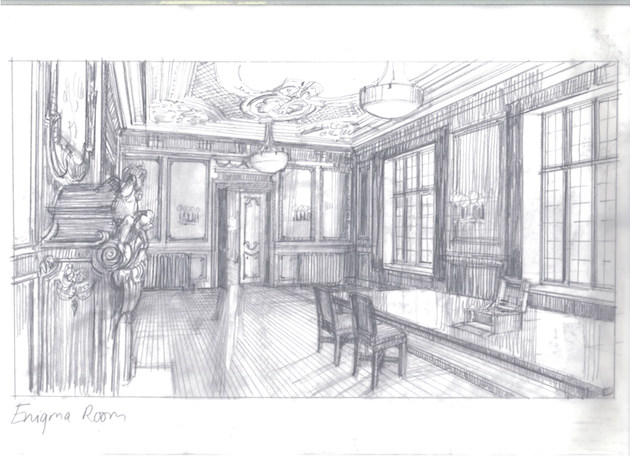

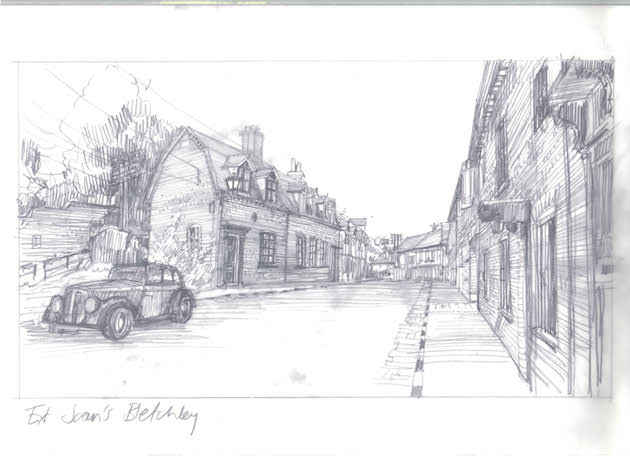

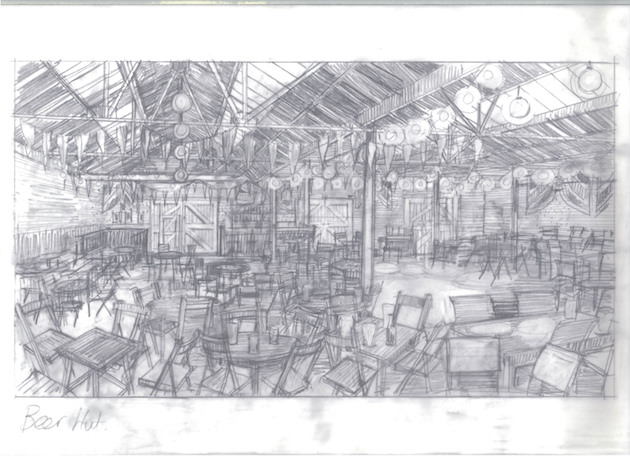

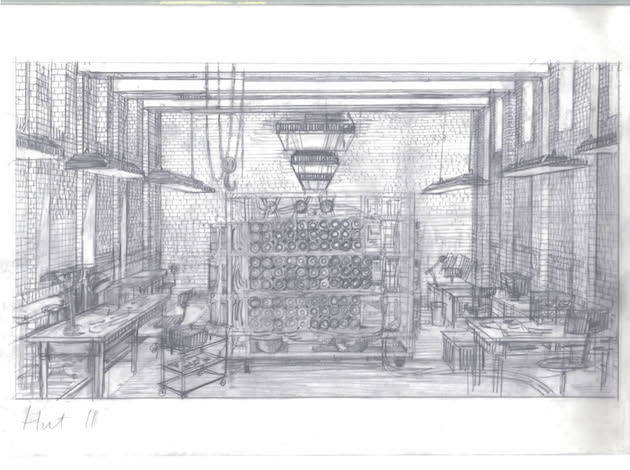

Many of those spaces were located at Bletchley Park, the United Kingdom’s Government Code and Cypher School, which during World War II was the headquarters of their efforts to crack Germany’s Enigma code. The Enigma code essentially made it impossible for the allies to track the Nazis' military movements. When Turing and his team were assembled at Bletchley, the allies were losing the war. It was in Bletchley’s various “huts” that the codebreakers labored, working day and night to decrypt the code. Djurkovic would create detailed sketches of these huts, and then recreate these designs, piece by piece, until they looked exactly right.

“You open a book into a world, and of course I knew who Alan Turing was, and had a notion of what was going on at Bletchley, but not in depth,” Djurkovic says. “So then you go and start studying their archives. I couldn’t begin to understand how it all actually worked, but you discover this whole other world, and you have to give the film an aesthetic. Actually, you have to give the film it’s own character.”

One way Djurkovic does this is by understanding the world of her film, but not necessarily following any set rules about the look of a specific period. “If you’re doing the 1940s, there are a few domestic interiors you see, like Joan’s [Keiry Knightley] parents house, that don’t have that floral wallpaper. I didn’t use any floral wallpaper, which would have been completely right for the period. All the wallpaper I use, especially the wallpaper in Turing’s Manchester house, look like Morse code. They’re dots and dashes, and of course nobody’s going to pick that out, and you’re not doing it to be picked out, you’re doing it for an overall atmosphere.”

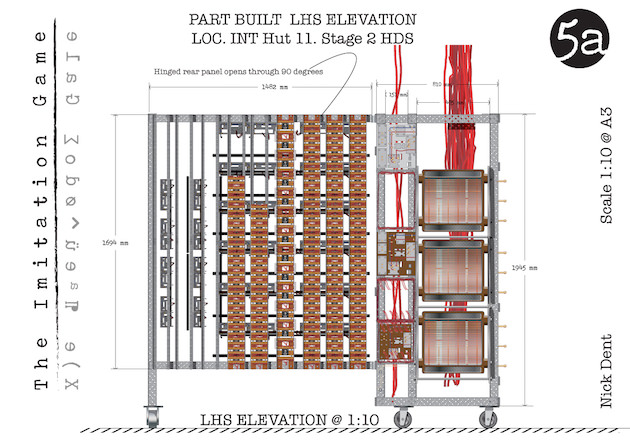

Among her many huge tasks creating the world of Bletchley Park, none were perhaps as daunting for Djurkovic as building the Bombe, Turing’s codebreaking machine, known affectionately in the film as Christopher.

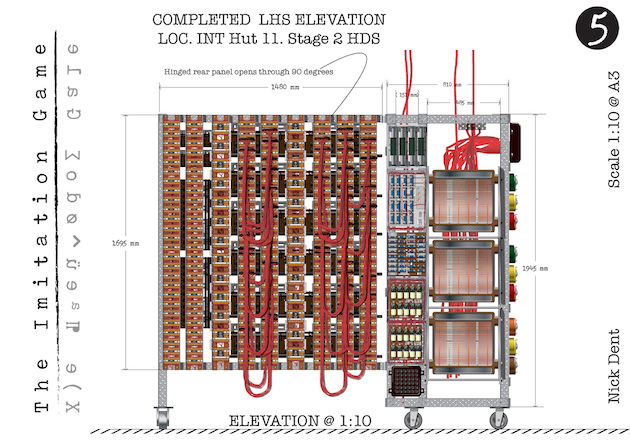

When Turing sketches his design for Christopher in the film, Djurkovic based those all of the real Turing’s work. “I didn’t make any of that up.” She also had one huge advantage; the actual Bombe, which has been kept in pristine condition. “We obviously had to create this extraordinary machine, and we had the one in Bletchley park which exists in a museum now. It’s a facsimile of Christopher, and it’s a working machine,” she says. “On our first scout, we went to look at it. The front of the machine we built is a direct facsimile, but ours is bigger. We decided to expand the scale, because the reality is the real Bombe is encased in a box, and it’s one big lump which just isn’t that interesting visually. But when Morten [Tyldum, director] and I went around the back and saw the innards, the workings of it, we made the decision then and there to make ours bigger, and to have it in two sections so it would open like a book.”

By expanding Christopher’s size, Djurkovic had to double the space it would occupy. The machine becomes a kind of totem of Turing’s monomaniacal genius; it represents everything that was incredible about his mind, but also how he shut so much else out in his life to build it. For Christopher to work as an emblem of Turing’s relentless, at times off-putting ambition, the machine Djurkovic and her team built had to fill up the space, and, it had to actually work.

“Christopher needed to work on several levels; it had to be believable; it had to work, meaning the dials had to move in sequence; and the rest of it had to be visually interesting,” she says.

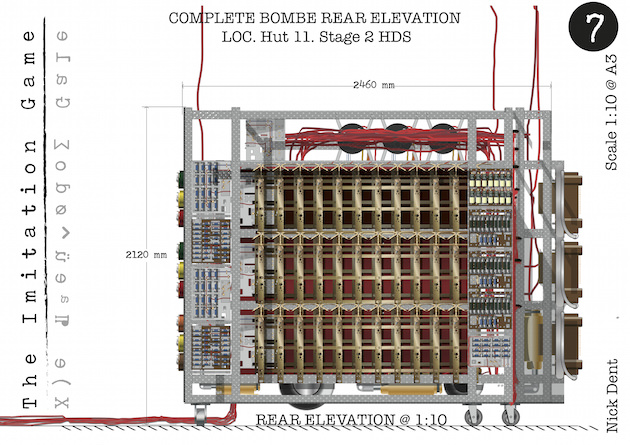

Actually building the thing required Djurkovic, supervising art director Nick Dent and his team, prop masters and a slew of interns armed with soldering irons and welding equipment to collaborate on every dial, wire, switch and button. “I had a very smart, technically minded art director who went to Bletchley and took lots of photographs and measurements and drew up what we had to build,” she says. “A prop like this could be unbelievably expensive, and we didn’t have the budget, so the pieces they had to move were sent to prop makers, and the immobile parts we made in house.”

Djurkovic says that luckily one of the art directors, Marco Anton Restivo, had great modeling skills, so they took him into the prop shop to help make Christopher. “Then lots of interns came in to do the soldiering and welding and sticking all these little pieces and components together,” she says. “And the components are a combo of things you can buy in a model shop, and they were combined with all these pieces that were period correct that our prop master found. It’s made largely out of bits form the 1940s.” Like the real Bombe, there are plenty of wires pouring out, but for Christopher, they added many more (painted red, to film’s key color) and were two-feet taller.

Djurkovich also had the challenge of building something that itself had to be built during the course of the film. “Because you watch Turing making Christopher, we had to figure out the process of it being built in several stages,” she says. From Turing’s initial sketches, which you see tacked up on his wall in Hut 8, to the final working machine, they had to design something that could be put together in pieces and moved around easily. “We had to incorporate into our design pieces that would be easy, and quick, to add and remove.”

Djurkovich says that when you get a script, every department sees their own particular problems right away. “I’m reading a script now that involves flashbacks to a dilapidated house in the 80s, which to me and my department means peeling paint and mold, and I’ve got the art director saying we have to shoot this in reverse. So getting all those fantastic finishes; the mold, peeling paint, etcetera, that takes longer than a fresh coat of a paint, but because it has to be shot in reverse it means we have to really plan it out.”

For the scenes involving the Christopher machine, there were tons of logistical questions that had to be solved, considering the machine is in varying stages of development, and those stages aren’t shot chronologically. On a Monday, Christopher is a working machine, but the next day of filming might have the machine as a pile of wires and metal. “The shooting of Christopher in Hut 11, all of those scenes were shot in a few days, you’re having to accommodate the efficiency of the shooting crew, and yet you’re seeing this machine in three different stages of finish, it’s just so much practical stuff that would not occur to the viewer,” Djurkovic says. “But that’s what I like about it, my job is like a giant puzzle, and you have to put the pieces together.”