Garrett Brown: An Interview With a Visionary—Part I

The major breakthrough moments in motion picture technology are fairly well known to the amateur film fan. There’s the advent of sound marked by the wondrous appearance of Al Jolson crooning “Mammy” in 1927’s The Jazz Singer. Technicolor, first developed around the same time, came into full bloom in the 1940s and 50s with the grand Hollywood Westerns and musicals. The first feature-length CGI movie was 1995’s Toy Story, which changed forever our expectations of animated storytelling.

The invention of the Steadicam® is not nearly so familiar to the movie-going public—if at all. Yet within the film industry, it is momentous. Revolutionary.

Introduced in the early 1970s by Garrett Brown, a Philadelphia-based cinematographer, the Steadicam is essentially a device that supports a handheld camera that allows the operator to film a subject in motion without the shaking that typically comes with handheld shots. Its adoption by the industry gave directors a new artistic freedom. No longer would they be restricted to track-mounted dolly shots or cranes to follow movement—nor burdened by the labor-intensive setups those required. Instead, the Steadicam operator could walk alongside, behind, or in front of the moving subject at will and capture stabilized imagery.

Brown’s invention made its feature film debut in 1975 in director Hal Ashby’s Bound for Glory starring Keith Carradine. Beginning from a position on a jib crane 30 feet in the air, Brown was lowered to the ground and then followed Carradine’s Woody Guthrie character as he weaved through a migrant camp scene with more than 900 extras for more than two minutes. Though Brown was unsure of the results until he saw the footage, the scene broke new ground. So much so, that when the film’s director of photography, Haskell Wexler, took home the Academy Award for best cinematography, Brown found both his invention—and his services—in great demand in Hollywood.

Brown himself was awarded an Oscar for Technical Achievement in 1978 for his invention.

The story of how Brown, now 72, developed such a breakthrough piece of technology is as remarkable as the tales he tells of employing it on movies like Rocky, The Shining, and Reds, to name just a few of the 70 plus features he has shot. (A resume sampler: Return of the Jedi, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Casino, Philadelphia, Marathon Man….) In part one of a two-part series, Brown talks to The Credits about the early days of the Steadicam, about calming his nerves high above the Bound For Glory set, and how a chance moment in Hollywood led to shooting one of the most iconic scenes in cinema history.

Let’s start in the late 1960s, when your company, The Moving & Talking Picture Company, was making commercials and short films for Sesame Street. What inspired you to begin working on a Steadicam?

I taught myself to be a filmmaker by reading film books from the Philadelphia library. And of course that made for some strange anachronisms, because all the books were absurdly out of date. So I taught myself, in effect, to be a 1940s filmmaker. And the equipment used in filmmaking in the 1940s were dollies and three-wheeled giant mic booms—this heavy, bulky equipment that I ended up buying. I had a little Bolex camera, and to move it smoothly, I had to use a dolly and a camera car. The dolly was about 800 pounds, and I had five pieces of rail (for tracking outdoors)—four straight and one curved—so you can imagine the absurdity of my dolly shots. They all went straight for a while and then curved, then went straight again; and they all lasted 24 seconds.

So you wanted to get rid of the dolly and use handheld?

Right. But I didn’t like the look of handheld because it’s shaky. The footage looks like a creature is holding the camera. I was conditioned to want my moves to be cinematically smooth.

An early version of the Steadicam featured a horizontal pole with a 16mm camera at one end, a counter-weight at the other, and a hand-cranked crane contraption. Tell us about that.

It was heavy and long; picture yourself carrying a ladder—if you hold a ladder at its center of balance it takes a lot of force to turn it—to pan it, or tilt it. I made a series of impossible shots with the crane and pole and showed the footage to Panavision and Cinema Products and both said, “this is amazing, the footage is terribly impressive, but you have to deliver in 35mm to be a success.” That’s what brought me flat up against the realization that this thing was a turkey—that it would never, ever work with a heavy camera. It was already enormous and the counterweight would have to be the same weight as the camera.

And that’s when you famously holed up in a hotel for a week to try to find a more workable version?

Right. I started over again out of desperation. We had a lot of money invested in getting it right and I needed to work my way through all the old ideas and drawings to create a more commercial version—to create a smaller and lighter version. I experimented with different kinds of rigging, balancing borrowed brooms and vacuum cleaners from the cleaning staff, running with my eyes closed down the corridors. I was just trying to get a feel for how it might work.

And what you emerged with is essentially the Steadicam we know today?

Yes. In fact, the original patent shows it is a combination of four things: One is to spread out the weight of each item that you’re dealing with—the camera, auxiliary, battery, and monitor—so that the center of the mass is pulled outside the camera and is accessible to you. Number two is to put a gimbal at the accessible spot so that you can hold the object at its center of balance but without any angular influence on it. The third item is to provide some sort of assistance for supporting on the body because it’s potentially so bloody heavy—you needed something to hold it like it’s in zero gravity that would allow you to move your arms freely.

And the fourth item in the patent?

The fourth item had to do with how the hell you would see through the lens! Originally it was a fiber optic cable [running from camera to the eye]. But that was dreadfully expensive. And, although it provided a brilliant image, it was stuck in front of one eye, meaning you had monocular vision while trying to move with it.

Stanley Kubrick saw some of the first 35mm demo shots you did. What was his response?

Well, first you should know that one of the great things about this particular invention is that you can see the results without giving away how it works. And we figured we would just blow away anyone in Hollywood with these impossible shots and they would have no clue how we did them. Kubrick saw the demo and sent a Telex saying marvelous things, including, “you can count on me as a customer.. .this should revolutionize the way films are shot. Oh, by the way, are you aware that a skilled counterintelligence photo interpreter can detect from the shadow on the ground some of the characteristics of how it might work?” We were horrified and ran into the screening room and sure enough, there were 14 frames with those shadows that none of us had noticed. So we cut them out.

Tell us how you connected with Hal Ashby for Bound for Glory?

That was due to Haskell Wexler, the great cinematographer. He contacted me in 1974 to shoot a Keds commercial using what we then called the “Brown Stabilizer.” So Haskell became our first customer. He had me chase after teenaged girls wearing Keds and the results were spectacular. Then Haskell was engaged to shoot Bound for Glory for his friend Hal Ashby, and he devised that insanely bold shot for me starting on the crane. It was my first-ever feature film.

What kind of prep did you do for that scene? Did you have a run-through or rehearsal?

No. I had a description from Haskell of what would happen in the shot: Carradine would get off of the truck bed and walk through the camp. I was to follow him all the way through and then precede him all the way back so that Haskell could preserve the angle of the backlight. The actual path was completely unknown to me in advance. The extras were instructed by loudspeaker not to look at me. They all obeyed except for one poor fellow in take two who didn’t recognize that I was a cameraman. I must have looked like some odd person carrying a sewing machine or something like that. The guy went right up to talk to Carradine in the middle of the take.

Did you know what you had by the time the shooting day was over?

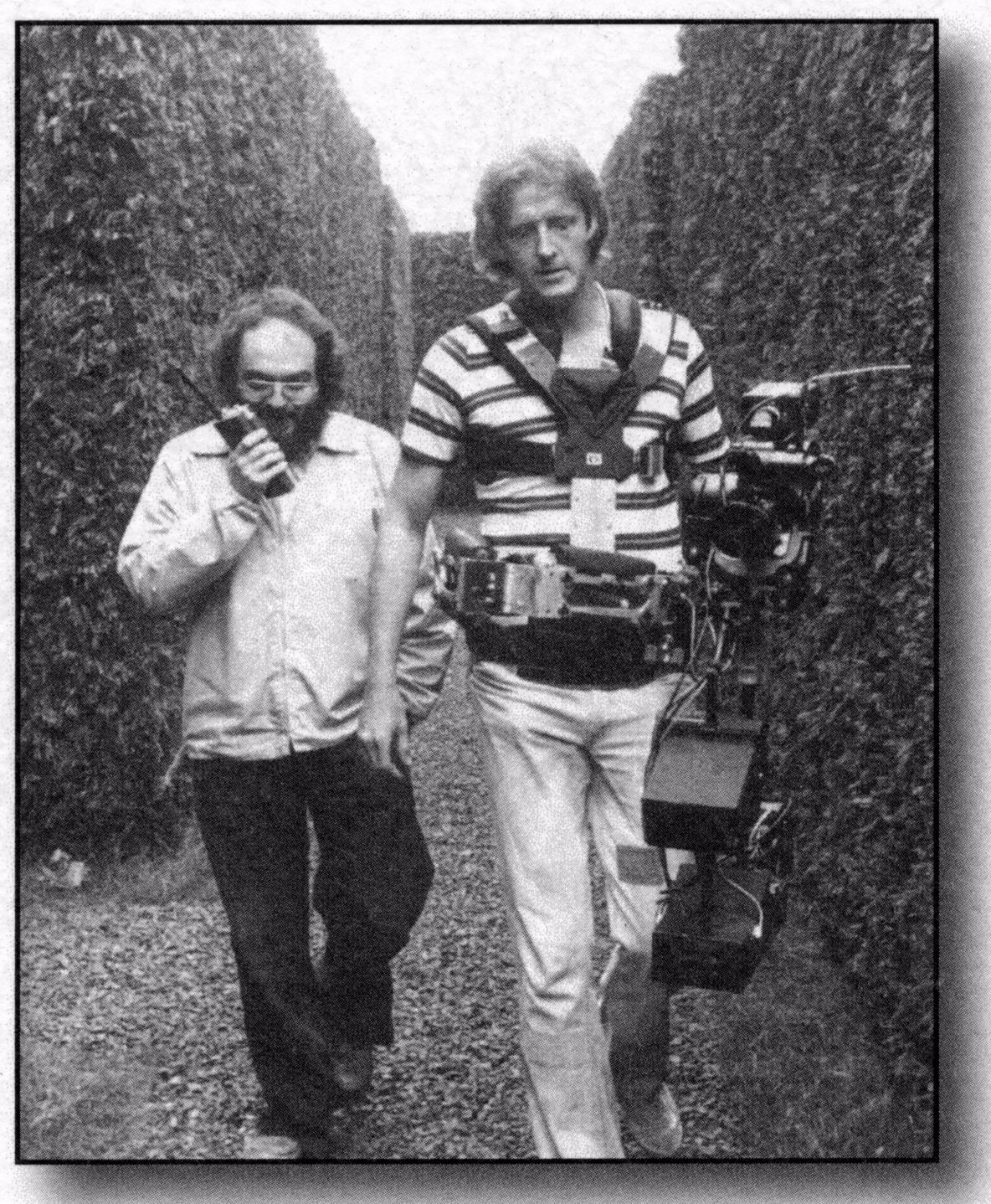

No. There were two takes before lunch and the second had the guy who had interrupted. The first was not very good. I was a bit scared standing 30 feet up in the air and Nick McLean, the regular camera operator, was with me to steady my nerves. He looked at my tiny little video monitor and said, “that’s funny, you’re shaking but the shot is still.” At lunchtime, he got me a beer and I was much settled down and we had one more take in the afternoon. And then they moved on. We figured we either had it or we didn’t.

You shot the now-legendary scene of Sylvester Stallone as Rocky running triumphantly up the steps of the Philadelphia Art Museum for director John Avildsen. And it was based on the very last shot on your famous 35mm demo reel?

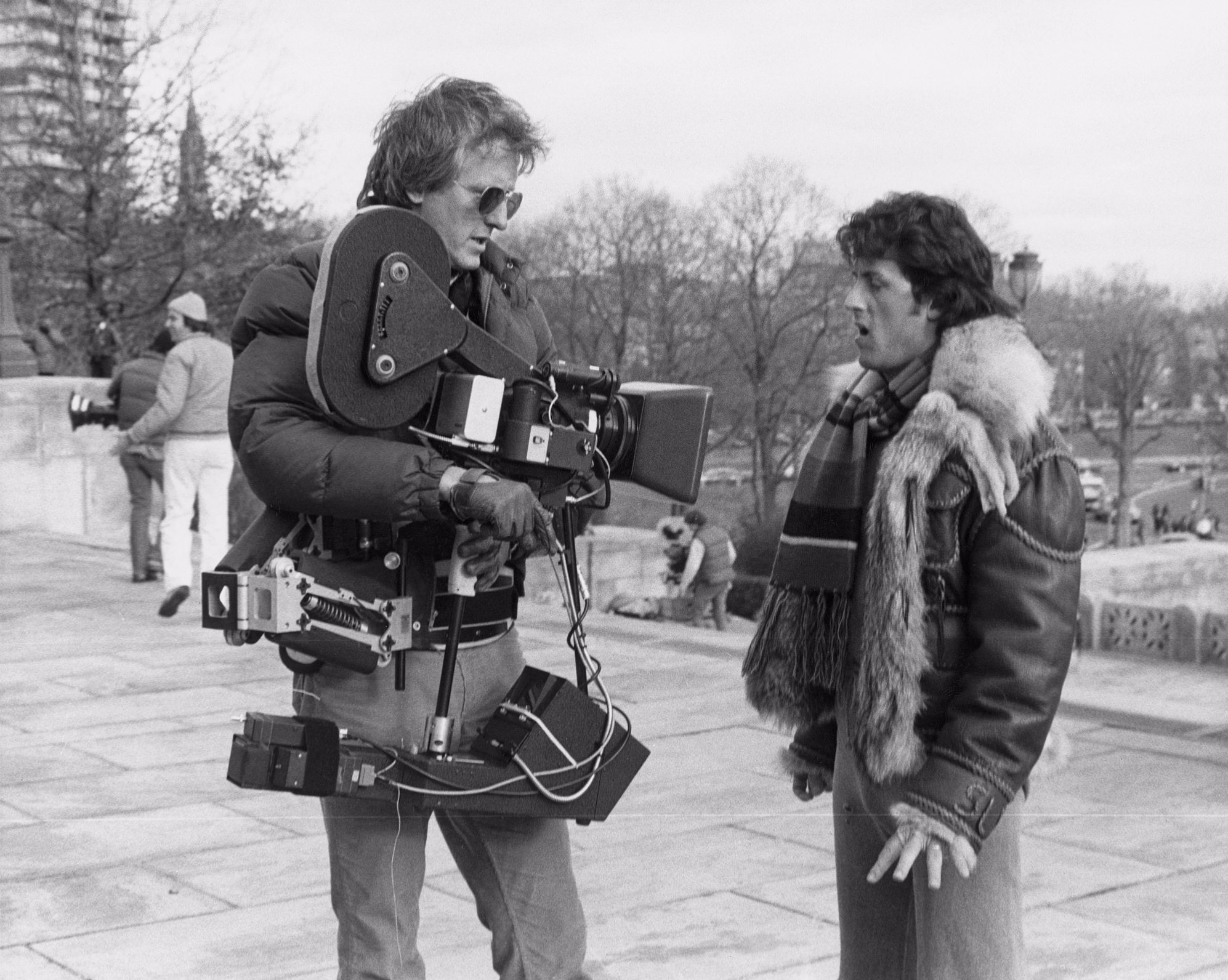

Yes. I had shot my [then] girlfriend, Ellen, running up and down the steps for the demo. Avildsen saw it and recognized his assistant, Ralph Hotchkiss—who I had hired for a shoot in Philadelphia—in the background. Avildsen contacted Ralph to ask, “where were those steps and how was that shot done?” I happened to be in Hollywood in Studio 15 at the time demo-ing the Steadicam for producer John Boorman. By coincidence, Avildsen, who was prepping to shoot Rocky, was in Studio 16. When I heard that, I arranged to come out from my studio come up behind Avildsen with my rig. I surprised him to say the least! And that’s how I ended up on that picture, doing the same shot over again with Stallone a few months later.

How many takes did you have for the scene?

Well, unfortunately it was cold that day, and my rig wasn’t running very well because it had been dropped, and a bent motor shaft inside the tube was rubbing. And that little motor just wasn’t adequate. So I had our director of photography, Ralf Bode, run behind me holding two car batteries with cables attached to the camera to try to keep it running. But Ralf’s legs were short, and he was heavily burdened, to say the least, and so he began to fall behind. One of the cables suddenly became taut and it put a serious jerk in the camera just at the triumphant moment at the top of the stairs. But we only had time for that one shot, that one take, and that was it. I’ve been slightly tormented by that imperfection of that shot all these years, but lately I’ve realized it doesn’t matter. It’s a great shot!

In part 2 of our interview, Brown describes working with Stanley Kubrick on The Shining, disappointing Warren Beatty, and the highlight of his career shooting with the Steadicam.