The Sports Coordinators on Upcoming Draft Day & Million Dollar Arm

Spittin’ and cussin’ and scratchin’ like a Major Leaguer doesn’t take a whole lot of skill for an actor. But hitting a home run when the director calls “action!” and making it look easy? That’s a whole other story. Enter the sports coordinator. These former top jocks train onscreen talent how to swing for the fences, catch a touchdown pass, or sink a game-winning jumper at the buzzer and convince audiences it’s athletically legit.

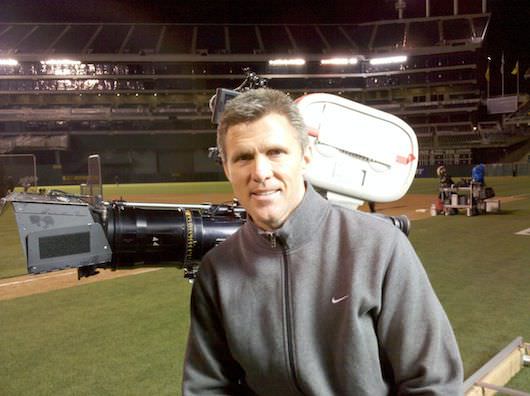

“I”m like a stunt coordinator but with sports,” says Mike Fisher, a former college and pro quarterback who has Moneyball, The Blind Side, and Remember the Titans on his résumé. “Say you have a football scene where a wide receiver is supposed to jump up, catch the ball and get flipped by a defender? Well, just like a guy who can flip a car, I can have a guy flip and land on his head.”

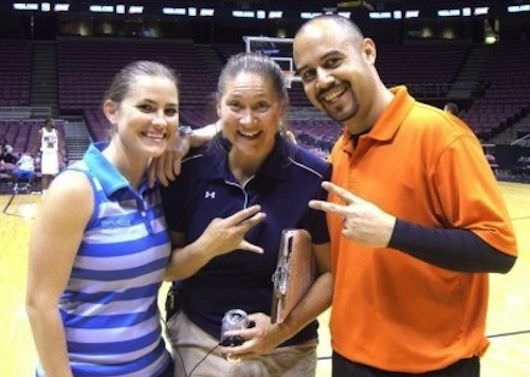

Aimee McDaniel of Game Changing Films sees herself as a sports choreographer. “We bring the actors’ athletic skills up and then we find athletes to be their doubles and tone their skills down so that they’re even,” says the one time college hoops star who counts Trouble with the Curve, Invictus, and Miracle among her credits.

With the113th Major League Baseball season upon us, and the latest testament to Fisher and McDaniel’s prowess arriving on the big screen soon (Fisher: Draft Day with Kevin Costner this Friday, April 11; McDaniel: Million Dollar Arm with Jon Hamm on May 16), The Credits talked with each coordinator independently about their jobs. Here’s how Fisher found his Blind Side redneck, and McDaniel turned Amy Adams into Yogi Berra.

Aimee, take me through your work on a typical sports movie, like The Longest Yard. What’s the first thing you do when you get a script?

Aimee: We break down the sports action for the director— how long it will take to get the actors up to speed and to choreograph the scenes? If the script says, "First and ten and then there's a handoff,” well, that handoff can seem simple, but you have to think about the camera angles and the story point. Is the running back hurt, for instance? Is the quarterback being selfish, is he not reading the play right? So it's not just the actual action of the handoff, it's everything that relates to that, including a suggestion of camera angles.

Where do you find your athletes?

Aimee: One way is with an open casting call and an announcement through social media. Then we try them out. Say it’s a football movie. On the first day we'll have everyone run a 40-yard dash, do some cone drills—you just want to see their athleticism. Then we’ll call them back the next day and group them into offense and defense, linemen, quarterback, skilled positions, and we'll get into more specifics, like how the quarterbacks throw. We'll take group pictures and present our choices to the director and producers. Obviously the hero team of the movie will be more specific in terms of ethnic breakdown, or the height and weight of what they’re going for, so that takes the longest.

Mike, when a casting director brings you actors for a film and they claim they can play, do you put them through their paces on the field?

Mike: Absolutely. In Moneyball, Chris Pratt (he played first baseman Scott Hatterberg) came through our casting director. I said, "Chris, meet me at the ballfield." We threw the ball around and we hit. Fortunately Chris had some athletic ability. Basically, when it comes down to the final three actors for a role and the casting director and the director like them all equally, I tell them to bring them to me on the basketball court or the football field or the diamond and I’ll evaluate them.

Is that how it worked with The Blind Side?

Mike: Well, there’s no real one recipe to casting. With Blind Side, they had already cast the lead role of Michael Oher (Quinton Aaron) but the rest of the actors came from tryouts in Atlanta. You remember the part of the redneck [player on the Milford team, #66], who taunts Oher? Well, I had six real good possibilites so I grabbed the director, John Lee Hancock, and said, here’s our best rednecks. They literally auditioned them right there on the field—we had them do their lines and ad lib and picked this one kid (Eric Benson) who [I believe] had never acted before and he ended up doing a great job.

Aimee, in Trouble with the Curve, you got Amy Adams to look she had been a catcher all her life despite her being afraid of the ball before filming began. How did you pull that off?

Aimee: We got lucky because Amy’s extremely competitive. I told her, "We got a double for you and we can use a catcher’s mask to cover her face." And Amy said, "No, for my character, I need to learn how to do this." So she gave us three days which doesn't seem like a lot, but it was a lot for her because she was in every scene of the movie. I had her work about two hours a day with [former Major League pitcher] David Elder, who owns a baseball training center just outside of Atlanta.

She had to pick up on things pretty quickly.

Aimee: She did. We started her off with tennis balls about two feet away just to get her comfortable. But she wasn’t just learning to catch and throw, she was learning to be a catcher. So we had to train her to keep her throwing hand behind her back while catching. We had her standing at first before crouching. We did that for the first hour, and she's like "Ok, I kinda get this," and in the next hour she gets better, and the next day, she says, "Ok, I feel confident. Let's put on a mask." After another hour, she says, "I'm ready, let's try a baseball." And then one of the balls went off her mitt and hit her face mask. She flinched, and you know those little moments in life where people go, "I'm done!”? She stood up, took the mask off and was like, "Wow, that sort of rattled me." I asked, "Are you ok?" She said, "That's it? That's the worst that will happen?" After that, she could not get enough. I had David throw some pretty good balls from 12 feet, hammering it, and she was ready to go.

Mike, you were a football player at SMU and later in the USFL and the CFL. How do you choreograph the specific skills needed for other kinds of sports movies?

Mike: I was the kid who was pretty much good in every sport growing up. I played one year of high school baseball and a ton of basketball. Now, there’s a million football or baseball or basketball coaches who know more than I do, but they don't have the slightest clue as to how that translates into making a movie. Having said that, let me tell you what I did on Moneyball. When I first got the job, I wanted to hire a technical adviser to assist me because, well, if you haven't played in the big leagues, you haven't played in the big leagues. So I hired Chad Kreuter, who was then head coach at USC. And you know, it’s funny. Many of the questions I get asked on a movie have nothing to do with what you might think. It would be like, "Hey, where would the pencil that the manager uses on the scorecard be in the 7th inning with two outs?" Any time I got a ridiculous question like that, I would say, "Ask Chad."

Aimee, you worked on the upcoming Million Dollar Arm, which is based on a true story about a U.S. sports agent who goes to India to find cricket players he can possibly turn into Major League Baseball pitching prospects. What was that like?

Aimee: I was in New Delhi for six weeks. The first four we were there just to train the two main actors, Madhur Mittal (Slumdog Millionaire), and Suraj Sharma (Life of Pi). A lot of the Indian players didn’ know anything about baseball. It was literally like teaching little league; "Here's a ball, here's a grip." But I’d forget about it sometimes, because I was out there with the glove and I’d just started throwing, and they just could not catch it. So it was breaking that down to a very basic level of how how to catch and step and throw.

Jon Hamm plays the sports agent. Did he get in on the baseball as well?

Aimee: He doesn't play any ball in the movie, but he obviously played as a kid. Plus, he’s a huge St. Louis Cardinals fan. Every time time they called "Cut!" he was out there throwing the ball around with the guys, he was really cute.

You seem to be able to handle almost any sport, Aimee. From football in The Longest Yard to baseball in Curve, to rugby in Invictus to ice hockey in Miracle. Which is the toughest sport to choreograph?

Aimee: I would say hockey is the hardest, but rugby is right up there, just because there's no real stopping point. Baseball is easy, you shoot north and south, you're behind the catcher or you're behind the pitcher. In football, you stop and reset every time there's a tackle. Hockey is not only on ice, but the puck is moving very quickly, and players just go and go. The same thing with rugby—it has 30 players on this huge field and it’s a continuous sport.

Mike, does anyone ever get hurt like in a real football game?

Mike: Part of my job is to make sure that doesn’t happen, but sure, you have people getting stepped on or they break a finger. They’re going all out.

Aimee, what’s your thinking about staged action?

Aimee: There’s artistic license. Look, the production company knows the sports fan will always be the sports fan. But what they want is the person who would never go to a sports movie. And I get it, it's a business.

How do you approach period movies, Aimee? Like We Are Marshall, which takes place in 1970?

Aimee: We have to do a lot of research to make sure things are factually right. The production might get the clothes and the hair right, but we have to get the players right. Like, they weren’t the 6’6” 280-pound guys of today, they were smaller. The way the wide receivers lined up—they weren’t standing like they do today, they were in a three-point stance. There’s a lot of stuff on YouTube you can watch, but fortunately, with We Are Marshall, Coach “Red” Dawson was still alive and we broke down the script with him. We asked “what were you thinking at this moment?” “What did you run?” In the first movie I worked on, Miracle, I got lucky. I got to meet the real coach Herb Brooks, which is one of the top five moments of my life. Talk about knowledge, he had it.