One Mama Bear, Two Cubs, and Three Filmmakers: Disneynature’s Bears

The world of wildlife filmmaking has changed dramatically in recent years. BBC’s Planet Earth set a new standard. High-definition cameras, stunning aerial shots, and time-lapse photography gave viewers incredible access to animal behavior never before caught on film. Disneynature’s Bears, which includes veterans of those productions, takes a different tack. Yes, it’s filmed in HD, and the gyro-stabilized shots from helicopters are spectacular, but the family-geared film has a different goal. Bears wants to show the bonds that tie together an animal family. John C. Reilly, who voiced the lead in Disney’s Wreck-It Ralph, narrates the tale with a well-balanced level of wit, choosing opportunities to point out how a lazy bear reminds him of his dad watching television or commenting on the mischievous antics of one of the cubs. The nature documentary also includes scenes that offer novel information about the mammals. In addition to eating salmon, bears turn over rocks to find eels, crunch on mussels, and dig up clams. In another scene, a wolf stalks one of the bear cubs, a moment that even the filmmakers were surprised to capture.

Bears director and producer Keith Scholey, an experienced wildlife filmmaker whose credits include Disneynature’s previous work African Cats and work on BBC nature documentaries, talked to The Credits to explain how their crew captured the life of a bear mother, who they name Sky, and her two cubs, Amber and Scout.

One thing that struck me is that Bears starts out by saying that half the bear cubs don’t survive their first year. The whole time I was thinking, ‘Is one of them going to die? Are they going to do that in a Disney movie?’ So I’m wondering: Did you actually follow the same bear family the whole year, or did you hedge your bets and follow multiple bear families?

By and large, it’s the same family. For certain key events, it is with others, but by and large we absolutely tried to stick with the same ones. At Katmai National Park, we tried to find the mother bear that was most comfortable with us. None of the bears are afraid of people, because they haven’t had any bad experiences with people. But you find some bears are actually far more relaxed than others. So we would say, the Sky bear found us, rather than we found her. Once you’ve got a very relaxed bear, you can just be a fly in the wall, and watch her life.

You say you’re a fly on the wall. But if that’s the case, how did you get inside the bear den for the opening shots there with the newborn cubs?

That was the only sequence that we actually did in captive conditions. If you used a wild den you could endanger the cubs. It’s sort of the prequel to the film. Everything you see after that is shot in the wild, but that is the one situation where it wouldn’t have been fair to the animals to have done that.

What was behind your decision to film in Alaska’s Katmai National Park?

For me, making the film here, in Katmai National Park, in Hallo Bay, was essential. What’s amazing about this place, Katmai, is that people haven’t lived there for 150 years now. Bears haven’t been hunted. In the 1990s, people started taking tourists in there, but were always incredibly careful about how they manage the bears. The bears never eat human food, so they never associate people with food. Bears basically ignore people. In my experience, that’s very unique to basically wander around the animal.

Tell me a little bit about how your team shot the movie and your role on set.

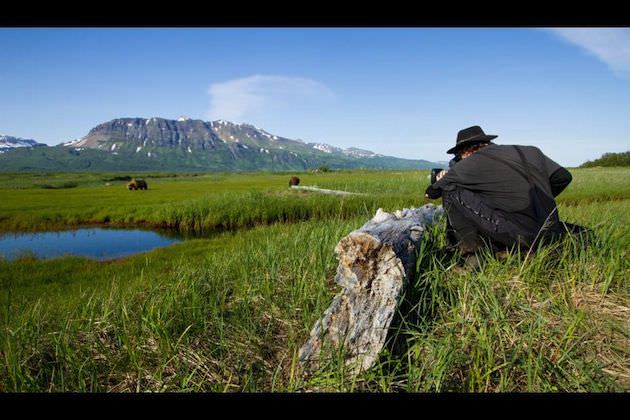

The basic filmmaking team has three people. Small is good, because you have less impact and disturbance. There’s a camera person, a field assistant to help carry everything, and one of the directors. There were three of us involved in directing the film: myself, [director] Alastair Fothergill, and [co-director] Adam Chapman. We made sure that one of us was always on location at any one time. There’s also a guide there to make sure our bear is kept happy. Because the bear season is so short, and they spend half the year hibernating, we had three camera crews out. Our job as directors was to make sure they were following the right story. We shoot so much footage that we edit as we go, to see how the story is playing out.

It sounds like you have a lot of experience doing wildlife films. What was different about this one?

Making these feature films for Disney is a very different experience than making a television documentary. It has to be a cinema experience: story, story, story is everything. In your normal wildlife documentary, you can say, ‘Well, we’ve had a look at the bears, so now let’s look at a seal,’ and so forth. In a Disneynature film, everything is centered on your characters. Anything that is not on message with the character story, you can’t really use. It’s fantastically creatively challenging, but they are hard. You need an awful lot of footage of your character, and an awful lot of behavior, to sustain a feature.

Are there any more Disneynature movies planned?

Next year, there’s Monkey Kingdom, which is about monkeys living in this temple in Sri Lanka. It’s kind of like the real Jungle Book. It’s very different story, but again a family-driven film about animal families. We keep thinking, ‘What’s next?’ You do need animals that are big characters and allow you to witness those things for these movies. That makes it quite a short list.

The bears are very humanized in this film, but they’re also still animals. Was there a balance you were trying to find between showing a character and an animal?

If you spend any time around wild animals, you know they’re all different. They all have their own personalities and emotions. The balance that we try to strike is that the film must always have respect for the animals. There’s a temptation to sometimes make the film funnier, and that’s fine. But it must never be done at their expense. You must be laughing with the bear and not at it. You also never want to do anything that’s scientifically wrong. You never want to talk about a piece of behavior being done for a reason that is not factually correct. The audience wants to feel like they’re part of the bear family, but they also want to feel confident that everything they’re seeing is truthful.

Over the two years you filmed, almost no bear cubs were born one year, because of a hard winter and poor salmon run. The next year, there was a baby boom. It’s very clear how much the bears depend on their environment. What’s the outlook for these bears? Are they in any danger from humans or climate change?

An American National Park is as good as it gets in terms of protection and laws. The Achilles’ heel of the bears is not what’s going on in the National Park, it’s what’s going on in the ocean. Where they’re most vulnerable is their dependence on the salmon population. If you look down the west coast of North America, a lot of the Canadian runs further south have died off. There’s a whole host of contributing causes, from pollution, deforestation, and overfishing of the ocean. The watchpoint is if the salmon stocks going to be adequately protected. That’s an international issue, not just an American issue. In that respect, Alaskan bears are a very good barometer of seeing how we’re doing internationally.

What do you hope kids and families get out of this film?

I hope that anyone, especially kids, comes away thinking that bears are absolutely fantastic. Bears get a lot of bad press. They’re seen as dangerous, mindless killers, which couldn’t be further from the truth. We hope people see the struggle bears and their cubs go through, and think that bears are superheroes. If people become bear fans, that can only help with conservation.