Poetry From Conflict: Writer-Director Musa Syeed on his Valley of Saints

Conflict zones have a long history of providing an amply angst-ridden backdrop for cinematic romance, but in his narrative feature debut, Valley of Saints, Musa Syeed takes a surprisingly lyrical look a largely untold conflict in India’s Kashmir region, an area that Indians and Pakistanis have fought three wars over during the past century. And the one-time documentary writer-director does it by exploring the idea of protecting Kashmir’s ecological beauty as a way of restoring stability to the region.

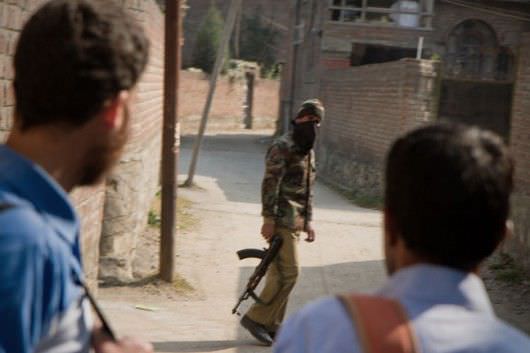

But the film is also two love stories, which Syeed shot during a real-life, week-long military curfew. The first centers on a tour boat driver who falls for a visitor studying pollution in Dal Lake, the one-time crown jewel of Kashmir, where a dwindling community of houseboat dwellers clings to old traditions while increasing violence and decay threatens to engulf them. The other is Syeed’s own love for a homeland he’d never been able to visit—his parents fled the area in the 1970s after his father, a political prisoner, was able to seek asylum in the United States.

In 2012, Valley of Saints had its premiere at the Sundance Film Festival, where it earned not only the World Cinema Audience Award, but also the Alfred P. Sloan Feature Film Prize, awarded to films that “focus on science or technology as a theme, or depicting a scientist, engineer or mathematician as a major character.”

On Friday, May 31, Syeed will host a screening and discussion of Valley of Saints at the Museum of the Moving Image as part of New York’s World Science Festival.

For a taste of what to expect, Syeed spoke with The Credits about how his award-winning film came to be, the beauty of filming in a war-torn region, and what legacy he hopes Saints will leave for his and others’ future work.

The Credits: Valley of Saints is your first narrative feature. What part of your documentary background did you want to bring to it?

Syeed: As a writer, I wanted to create a world that didn’t exist, but still create a story that felt very real. In 2009, I spent three months in Kashmir, looking for real-life inspiration on the ground. It was my first real exposure to Dal Lake and Kashmir as an adult.

How did you set about doing that?

My highest level intention was to reconnect with Kashmir and to tell a story that wasn’t just about the politics—because that’s really all I knew growing up—but to tell a story about the every day lives of people there, to turn their struggles and their relationships into something more human. Then I just tried to be as open as possible to discovering however the story might manifest itself to me.

You lived on a house-boat in the middle of Dal Lake. Was that your first exposure to pollution in the region?

I’d grown up hearing how beautiful the lake was from my parents. In their minds, it was the most beautiful place in the world, even though they haven’t been there in 20 years. But then a few years ago, I started to read reports about the environmental problems Kashmir was facing and that all of these beautiful landmarks and lakes and forests and rivers I’d heard so much about were being polluted or mismanaged. At the same time, I’d been wracking my brain trying to tell a story about Kashmir that wasn’t just about the politics. I didn’t want to ignore it. I just wanted to look at Kashmir in a different way. When the romanticism of my parents’ stories started fading away, I started thinking about the movie as an allegory, about how the environment is a reflection of society and the human condition that inhabits it.

The main female character in the film, Asifa, is a scientist who has come to the area to study water pollution. Were you inspired by scientists you met?

There are a lot of people on Dal Lake who are doing similar work. The problem is that there are limited resources and a lot of the government funding isn’t going towards the most constructive projects. Instead of investing in cleaning up Dal Lake, the government is allocating funds to move the people living on the lake elsewhere. I think that’s one solution, but it’s not a sustainable solution. I think if there was a more community-based approach to solving these problems, it might provide a more sustainable solution. But because of the corruption and instability of the region, it’s hard to get people to work on solutions like that. But there are definitely people on the ground there who are looking to do that. And they informed and inspired the work in different ways.

How much did you run things past your family while you were developing the movie?

Not too often. I have a lot of family still there, but honestly, I feel like they were trying to protect me from things. My family in Kashmir is upper middle class and they’re in their own circle and I wanted to see beyond that. The boat people who live inside the lake became my new family. They weren’t people I knew before, but I spent a lot of time with them and they eventually took me in as one of their own. It was partially because I was willing to spend so much time with them, but also, I think it was seeing this Kashmiri kid who didn’t know anything about his culture and taking pity on me and wanting to teach me something. They took care of me, they fed me, they housed me. The collaboration with the community became a lot more than just a film crew coming in and doing our own thing. We went with such a small crew from America, just myself and my producer and my cinematographer, if it wasn’t for this community that we created, we wouldn’t have been able to make the film.

Between researching the movie in 2009 and when you returned the following summer, violence in the area had escalated considerably, and a curfew had been imposed. Did you consider postponing your shoot?

At first, we were hesitant, but ultimately we felt even more compelled to film it during that time to capture some of the uncertainty that Kashmiris live under. I threw out the script that I had, because we weren’t really sure what we were going to be able to shoot. I had to rewrite it in a more confined way to reflect the situation.

Did you always intend to cast your leads locally?

The female lead was actually going to be played by an American actress, and half of the movie was going to be in English because she was supposed to be from America. But I’m happy that we ended up with an all-Kashmiri cast. The Kashmiri language is a dying language that’s very rarely spoken in film. When we submitted Valley of Saints to IMDB, Kashmiri had to be added as a language option, which I’m proud of. And it’s funny because I don’t even speak the language! I just learned enough to understand the dialogue of my film.

How did you find your lead, Gulzár, in the first place?

I was visiting the lake every day for research, talking to the boatmen and interviewing them informally. He’s like the secretary of the boatmen’s union, so he’s something of a public figure. Because he can read and speak English well, people come to him to get help with understanding their doctors’ prescriptions and dictating letters and things like that. When I mentioned I was looking for someone to interview, everyone pointed to him.

Was he helpful with the script writing?

Behind the scenes, Gulzár was rowing us on his boat to the location every day, getting extras in line, stuff like that. Translating the script is what I originally hired Afzal, the other male lead to do. He is a journalist in Kashmir, so his grasp of language is really great. Throughout the rehearsal process though, he and Gulzár developed a deep, funny, and unique chemistry, and a very believable friendship. So I decided to cast him in the film, especially when everything else sort of fell through. He and Gulzár basically translated their lines themselves, which I really encouraged them to make as colloquial and informal as possible. I wanted the actors to feel comfortable with their words and to take some ownership of the script.

Were people in the area excited to have a film shoot going on?

I think people were just happy to have us around. Because there was this curfew, there weren’t that many tourists around, and we became entertainment for the locals. They’ve seen Bollywood productions come and go very quickly, so when they saw our tiny little camera and our tiny little crew, I don’t know how that stacked up, but I think they appreciated that we were eager to work there for an extended period of time and to really understand the area.

Wasn’t permitting an issue?

We got permission from the Indian government pretty quickly, thanks to a cousin who is a journalist in Delhi, but part of the permitting stipulated that we would allow a handler to come with us. We just never told them when we started shooting, and that got us out of having an escort. We weren’t really sure what was going to happen, so we tried to keep a low profile. We had to bribe a cop to not pester us and another undercover police officer who had followed us home one night.

Considering the unrest in the area, it sounds like thing went smoothly?

My cinematographer broke his leg and had to finish the last half of the movie on crutches, and we got rocks thrown at us. But all in all, we didn’t want to put ourselves in harm’s way, and I didn’t want to put anyone in it, so mostly we were able to stay out of trouble.

You won the Sloan Prize and the Audience Award at last year’s Sundance Festival, which puts you in an enviable spot. What’s up for you next?

I’m developing a couple of projects—one in New York and one in the Middle East— and we’ll see which one takes off first.

Is shining a light on unsung communities a big motivation for the choices you make?

Coming from an immigrant background, I like the feeling of being connected to so many different parts of the world and not feeling constrained by any one place, and also knowing that there are so many parts of the world whose stories don’t get told, especially in America. So yeah, I want to do stories about places we don’t understand or that we don’t know anything about.

Featured image: A still shot from 'Valley of the Saints,' courtesy of Musa Syeed.