The Incredible True Story Behind The Sessions: A Conversation With Director Ben Lewin

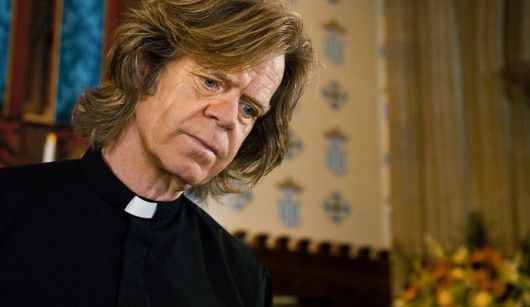

The Sessions tells the story of Mark O’Brien, a man confined to an iron lung for most of his day and who is determined, as he nears 40, to lose his virginity. The premise could be mistaken for a potential comedy or a melodrama. It was neither. In fact, The Sessions has been the focus of serious Oscar buzz ever since reviewers across the country fell in love with it in early November. John Hawkes (Winter’s Bone, Martha Marcy May Marlene) stars as O’Brien; Helen Hunt plays Cheryl Cohen Greene, the sexual surrogate who teaches O’Brien how to reach and control his orgasms; and William H. Macy channels Father Brendan, a Catholic priest from whom O’Brien seeks dispensation and counsel.

When writer-director Ben Lewin first came across polio victim Mark O’Brien’s 1990 article, “On Seeing a Sex Surrogate,” he was immediately intrigued: A 38 year-old man confined to an iron lung for 80% of his day, and largely paralyzed from the neck down, seeks to lose his virginity. Though Lewin had also suffered from polio as a child, as a filmmaker, what truly drew him in was the possibility of telling a thoroughly original and engaging story of a journey that essentially takes place between two people in one room.

We spoke with Lewin about the incredible true story about the film, making a fantastic film about two people in a room, and ditching fantasy sequences in favor of the chemistry happening on screen.

THE CREDITS: You first read Mark’s story in late 2006. When you read the article, as a filmmaker, what was your first instinct?

BEN LEWIN: When I started imagining it as a film, my first thought was, “Wow, wouldn’t it be great if Mark O’Brien could play himself?” until I learned that he died in ’99. I contacted the newspaper that published the article, and the editor there told me that his girlfriend, Susan Fernbach, owned the rights to the article. That’s how I discovered that in the last years of his life that he had this wonderful relationship with a woman, which added a very ironic coda to the story for me. My wife and I went up to Northern California to spend the weekend with Susan a few months later.

Did the project begin then in earnest fairly quickly?

We really began to like and trust each other right then. We were very mindful from the outset, that one of the really attractive parts of the project was that it was makeable. It was a very powerful, dramatic story, in a very compact form. Two people in a room usually amounts to a boring movie—but not in this case. We visualized a film that we could artistically control, because it wouldn’t cost us a lot of money to do it. I began the writing process as soon as I met Susan.

How long was it before you met with Cheryl, O’Brien’s real-life sexual surrogate?

The effect of meeting Cheryl was that it really became a relationship movie in my mind, the relationship between Mark and Cheryl. I realized I had two very fascinating characters and it became a journey film, not just a biopic.

John Hawkes spent countless hours lying on a gurney, contorting his back in ways that ultimately injured a disc. How important was physicality in your casting?

One of my big concerns was finding someone who could play Mark without a body double, computer-generated imagery, or a lot of optical trickery. John had the advantage of being of very slight build, but he also went to enormous lengths to do what was physically necessary to be that character.

Obviously there were a lot of challenges in finding the right Mark, but was casting Cheryl just as daunting?

Yes, every bit. When you’re casting, you’re re-writing the script in a way and defining the demographic of the movie. I wanted to make Cheryl as real as possible, and I needed someone really intelligent to convey the paradox of her situation: a middle class soccer mom representing family values who also has this really unusual occupation at the same time and having to tread this tightrope of being physically involved with a client and caring about the client, but not wanting to get emotionally involved. That’s a very complex and layered character, so you need an actress who really appreciates that and is prepared to tackle it without thinking it. It’s one thing to play a complex character; it’s another thing to do it as if you’re not even thinking about it. I put a lot of effort and thought into the casting. To me it’s the most stressful and the most exciting part of film production.

How involved were Susan and Cheryl in the casting?

Every now and then I’d bounce ideas off them, but when I’m casting, in the same way as when I’m writing, I need to be focused and really have a sense of what I’m doing as a filmmaker rather than getting too many opinions.

Did you tend to use the real-life folks more while you were writing then?

Yes. Cheryl is a wonderful character and I think without her collaboration, and without Susan’s, this would have been a very different film, and much the poorer. I found them invaluable resources to my writing. During production, they were also available to the actors, the art department, and anyone else interested in detail.

The Father Brendan character is such an important part of the structure of the screenplay itself.

His character is really invented, because I didn’t know who he was, aside from the text of Mark’s article, where he talks about a particular priest that he consulted to get some kind of blessing from. I found the idea of a hippie priest in Berkeley quite plausible, and I also find the idea of someone working in that job being profoundly humanitarian and not imprisoned by dogma, equally plausible. I think Father Brendan is also kind of a Greek chorus, an outlet for Mark’s inner voice.

His curiosity about Mark’s sexual experiences also brings lightness to the film.

Ironically, these are both characters for whom sex is kind of a no-man’s land, so there is a funny aspect that neither of them have a very experienced take on the subject.

What parts of Mark’s story were you most interested in telling?

In 1999, Jessica Yu made and Oscar winning documentary on Mark called Breathing Lessons, where she used his poetry as a connective device to tell his story. Listening to the way his poetry was used in that film stimulated me to read all of his poems and to use as much of it as I could to amplify the narrative. I was prepared to have technical errors with his body. What was more important was getting Mark’s essence as a writer and a thinker, and particularly his lust for experience.

Did anything particularly surprising come about during filming?

The biggest surprise came in the editing. I had filmed some fantasy sequences that were suggested by Mark’s article, but I found that the relationship between Cheryl and Mark, and then between Helen and John, played in such a real way that I couldn’t use them, because they felt like they belonged in another movie. I was worried about the film being constantly trapped by filming a horizontal guy, and I initially thought the fantasy sequences could lighten things up, but we dumped them when we saw how authentic their relationship played.

Sexual surrogacy isn’t a widely known field. Do you see your film having the potential to spark interest in it?

Amazingly, at quite a number of screenings, someone has stood up and said, “I’ve been a sexual surrogate for twenty years and I finally feel comfortable talking about it.” Even if it’s an unintended effect, I do think the film has generated curiosity about that very unusual profession, and I hope that it’s given it some dignity and legitimacy.

Featured Image: Director Ben Lewin chats with William H. Macy on the set The Sessions—courtesy Fox Searchlight.